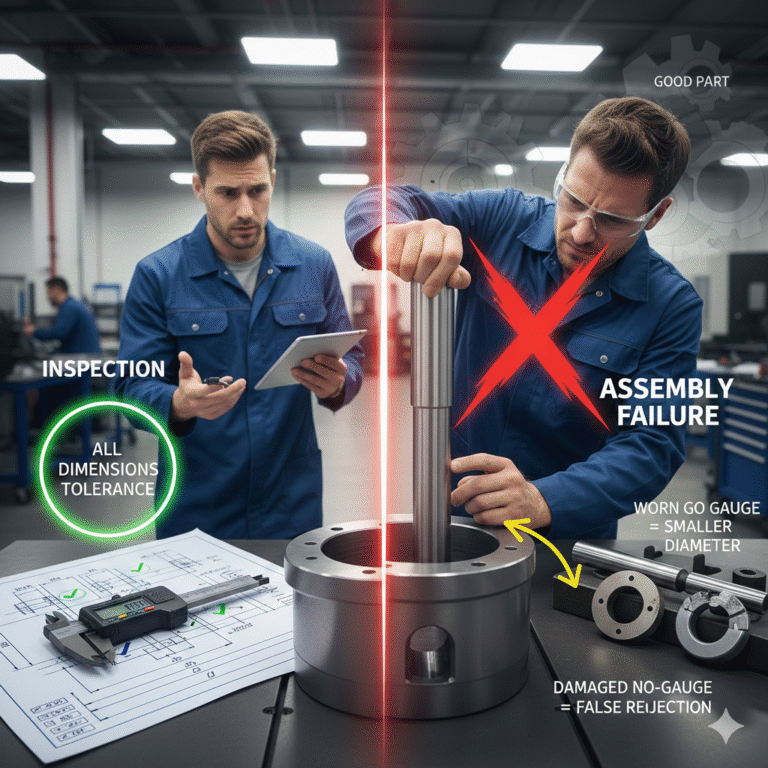

In machining and manufacturing workshops, many engineers have encountered the following paradox:

The inspection team insists: “All dimensions are within tolerance.”

But at the assembly station, the shaft simply cannot enter the hole—no matter how much force the technician applies.

Drawings are correct, machining offsets are correct, and measuring tools appear normal.

Yet assembly still fails.

Conversely, there are situations where a part considered out of tolerance during inspection fits perfectly in assembly. Sometimes day-shift operators say a gauge feels “fine,” but night-shift operators say it feels “tight.”

The root cause often turns out to be surprisingly simple:

👉 The GO gauge has worn smaller, or the NO-GO gauge has been damaged or enlarged.

👉 As a result, the measurement does not reflect the true functional size of the part.

The seemingly “mystical” inconsistencies in machining and assembly all point to one truth:

In many cases, assembly success is not decided by the machine, nor by the operator—

it is determined by the GO/NO-GO gauge, the true functional boundary of the fit.

This article explains, from an engineering perspective, why GO/NO-GO gauges remain the most cost-effective, reliable, and efficient quality protection method in industrial manufacturing.

1. A GO Gauge Passing Does Not Guarantee Assembly Compatibility

Many beginners assume a GO gauge only checks whether a diameter meets its lower limit. If that were the case, more precise tools—micrometers, dial bore gauges, or air gauges—would provide higher accuracy.

The actual value of GO gauges is based on the Taylor Principle:

A GO gauge is a functional replica of the mating part.

A GO plug gauge is intentionally made long—not for ergonomics—but to simulate the real engagement behavior of a shaft entering a hole.

During insertion, it does not only check size; it simultaneously checks:

Straightness

Roundness

Taper

Local diameter deviations

“Bell-mouth” or “barrel-shape” distortion

For example:

A hole may show correct diameter readings at three measuring points, but if the hole is slightly curved or has variations along its depth, a three-point internal micrometer may not detect it—

but a long GO gauge will immediately reveal whether the part can truly be assembled.

👉 A GO gauge verifies functional assembly limits—not just geometric size.

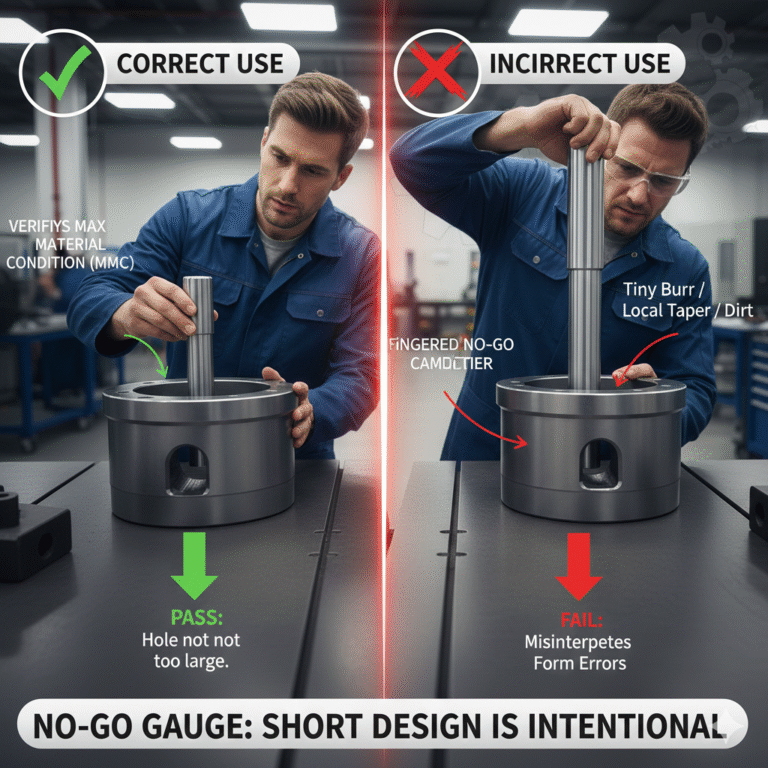

2. Why NO-GO Gauges Are Designed Short on Purpose

The NO-GO gauge checks whether the feature exceeds its upper limit (i.e., whether a hole is too large).

Its short design is intentional:

A short NO-GO gauge minimizes the influence of form errors.

If a NO-GO gauge were too long, it could falsely jam due to:

A tiny burr

A machining mark

Local taper

Dirt or debris

This might incorrectly classify a good part as nonconforming.

A short gauge bypasses those localized issues and focuses solely on its purpose:

👉 Determine whether the part violates the Maximum Material Condition (MMC).

The simpler and shorter the NO-GO gauge, the more accurate and consistent the judgment.

3. Two Types of Gauges Most Commonly Misused in Workshops

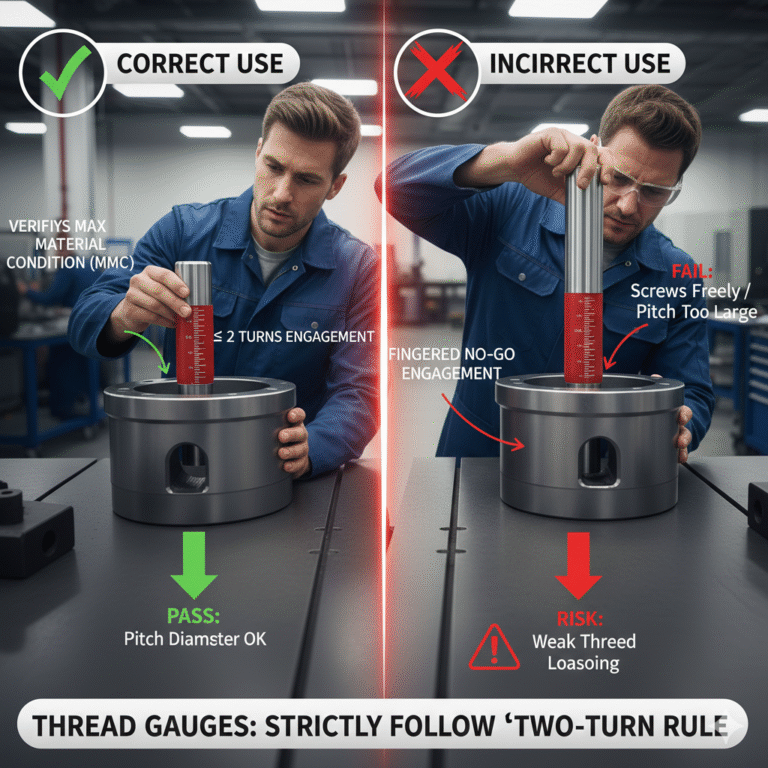

3.1 Thread Gauges: Strictly Follow the “Two-Turn Rule”

A thread NO-GO gauge evaluates the pitch diameter, not how “smooth” the thread feels.

International standards clearly state:

A NO-GO gauge may engage,

But must not advance more than two turns.

If a NO-GO gauge screws in freely:

✔ Pitch diameter is too large

✔ Thread strength decreases

✔ Risk of loosening or stripping increases

Yet many technicians still believe “the smoother, the better,” leading to serious acceptance mistakes.

3.2 Caliper-Type Snap Gauges: Operator Force Determines the Result

Snap gauges measure shaft OD. Because the C-frame has slight elasticity:

Forcing a shaft into the gauge opens the jaws slightly

The gauge “appears” to pass even if the part is oversized

Thus the classic workshop scenario:

Beginner pushes hard → “Part is OK”

Experienced operator uses light force → “Part is NOT OK”

A snap gauge must be used with:

✔ Light, consistent pressure

✔ A slight “dragging” feel

✔ No forcing or squeezing

👉 When force is involved, accuracy disappears.

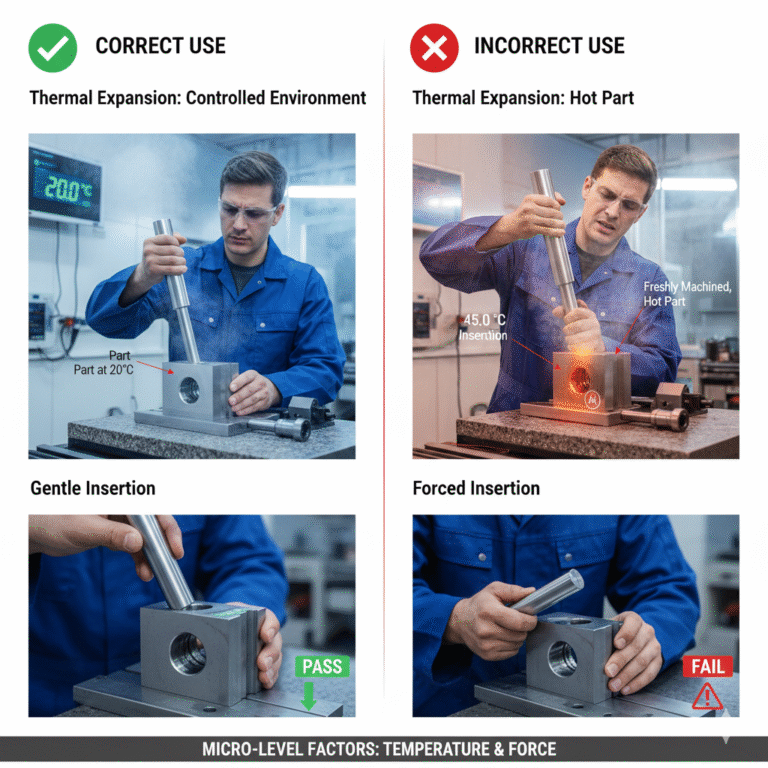

4. Micro-Level Factors That Greatly Distort Gauge-Based Measurements

4.1 Thermal Expansion: A Hidden Trap

Freshly machined parts may be 40–50°C, causing:

Shafts to grow

Holes to expand

A GO gauge may pass easily when the part is hot—but once it cools back to 20°C, the fit becomes too tight.

For tolerance levels IT6 and tighter, measurement must be done in a controlled environment.

4.2 A GO Gauge Should “Fall In,” Not Be “Pushed In”

Correct operation:

Vertical measurement: gauge drops in under its own weight

Horizontal measurement: guide the gauge with fingertip pressure only

Any shaking, twisting, or pushing indicates the reading is no longer trustworthy.

👉 In micrometer-level inspection, less force always means more accuracy.

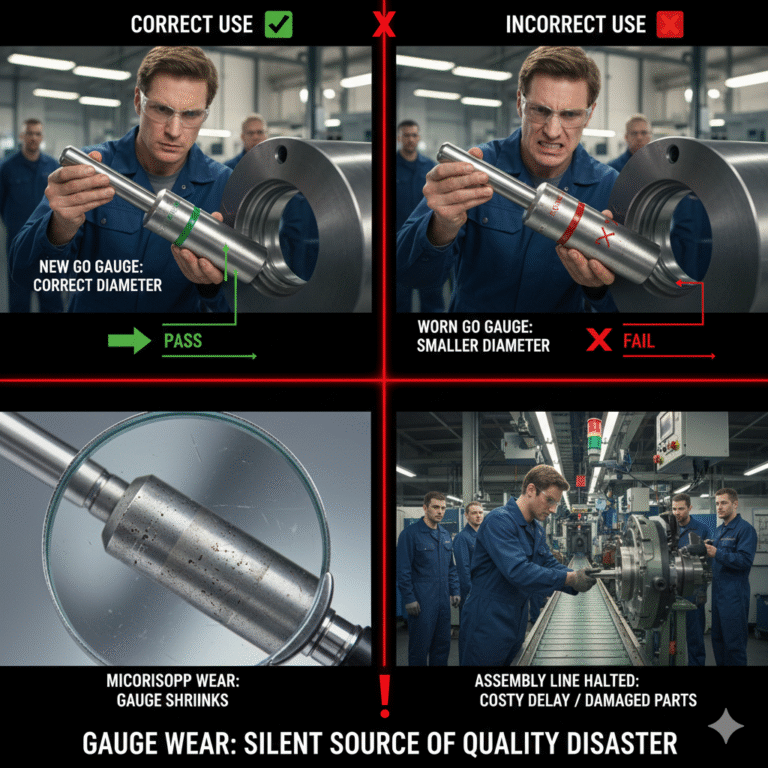

5. Gauge Wear: The Most Common and Most Dangerous Cause of Incorrect Inspection

GO gauges wear faster than NO-GO gauges because they are inserted more frequently and with more contact length.

Once worn:

GO gauge becomes smaller

Oversized or undersized holes are incorrectly accepted

Faulty parts move to assembly

Large-scale assembly failures may occur

Typical failure chain:

Worn GO gauge becomes undersized

Small holes are mistakenly judged “OK”

Assembly line experiences intermittent jamming

Production is delayed or halted

Sometimes expensive equipment components are damaged

Therefore, gauge management must be systematic:

Establish gauge inventory and traceability

Perform regular calibration

Track wear trends

Inspect gauge surfaces for scratches and corrosion

Apply special control to critical gauges

👉 A worn gauge is a silent source of quality disasters.

6. Conclusion: GO/NO-GO Gauges Are the Hidden Backbone of Industrial Quality

GO/NO-GO gauges remain indispensable in modern manufacturing because they uphold the most fundamental principle of industrial production:

Interchangeability

They require:

No power

No software

No programming

No calibration complexity

Yet they convert abstract tolerance concepts into the simplest, most intuitive decision:

👉 Pass / Do Not Pass

With the lowest cost and highest reliability, they filter out most assembly-related defects long before they reach the customer.

GO and NO-GO gauges may look simple,

but they are the invisible framework that ensures stability, consistency, and functional integrity in mechanical manufacturing.