Signal drift is one of the most frustrating issues in industrial automation.

It won’t trip the system, won’t raise alarms, and won’t obviously fail — it simply “moves a little” over time.

A slow slope appears in the trend, the analog value gradually shifts, and the PID loop starts behaving strangely.

Engineers may spend days chasing the drift—replacing instruments, checking programs, measuring terminals—only to conclude:

“It’s drifting again.”

Signal drift is subtle, persistent, and often overlooked. It doesn’t cause immediate failure, yet it silently degrades the entire control system.

This article explains — in true engineering terms — why drift happens, why it’s hard to diagnose, how to quickly pinpoint the cause, and how to permanently eliminate it.

These are not theoretical concepts, but practical insights gained from real industrial experience.

1. What Exactly Is Signal Drift?

Most instrument failures are sudden:

If it’s broken, it stops. If there’s an alarm, it shows. If there’s a fault, it trips.

But drift is different.

It is a slow, continuous deviation:

A few milliamps off today

Several percentage points off in a week

Control deviation in a month

An unreadable trend curve in six months

The difficulty lies in this:

Drift is rarely caused by a single component — it is the accumulated effect of slight changes along the entire signal chain.

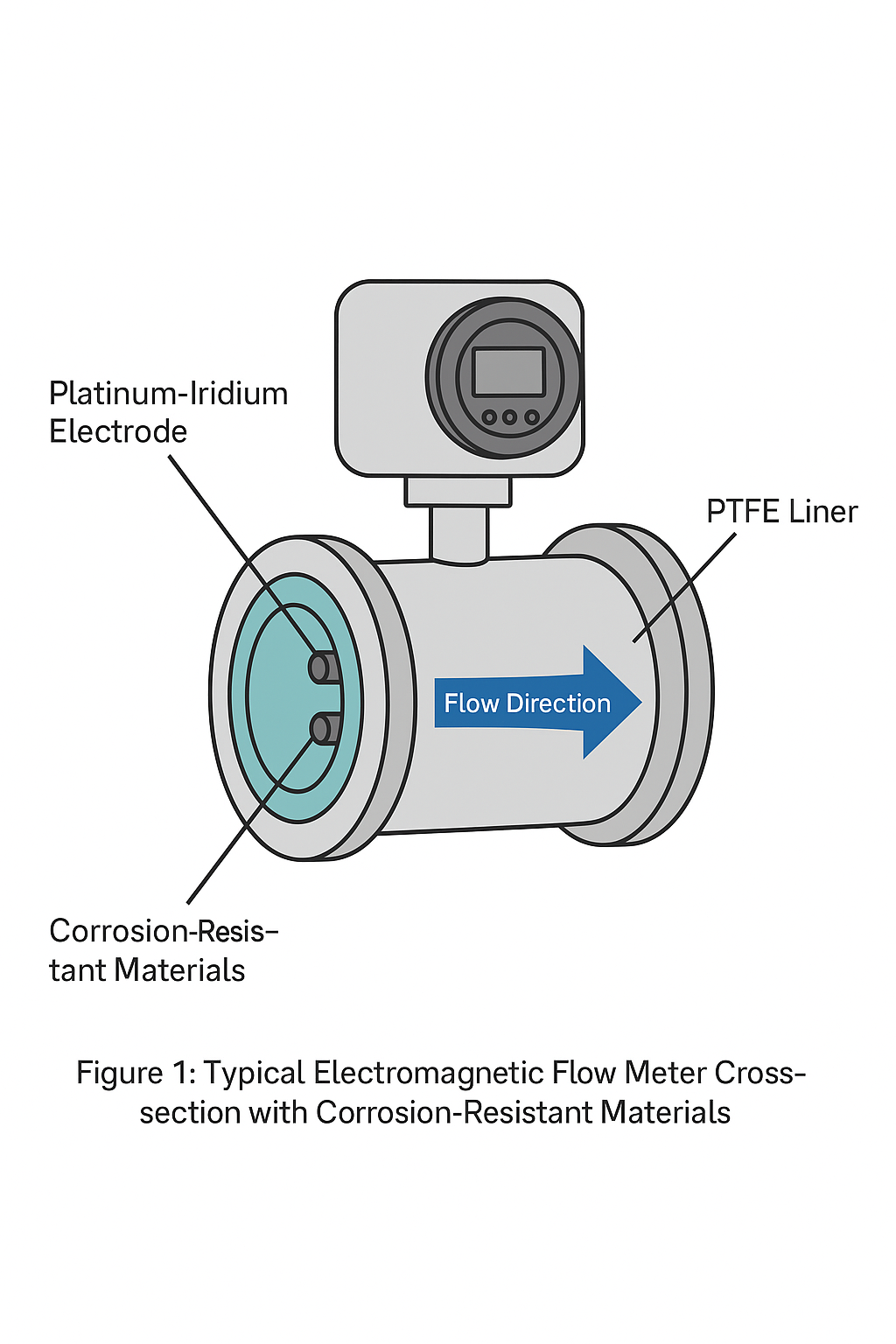

A typical analog measurement chain includes:

Instrument → Transmitter → Cable → Junction Box/Terminal → Isolator → PLC AI → Power Supply → Grounding → Ambient Environment → EMC Interference

A small deviation in any single part can gradually accumulate into drift.

This is the “mysterious” nature of drift.

2. What Causes Signal Drift?

Although the symptoms vary, most root causes fall into the following categories.

2.1 Ground Potential Difference — The Most Common Hidden Cause

If the PLC and instrument do not share the same reference ground, even a few tens of millivolts difference can cause the analog signal to shift.

Typical symptoms:

Value jumps when motors or pumps start

Long cable runs amplify the drift

Installing an isolator immediately stabilizes the signal

If you see drift that “just doesn’t make sense,” start with grounding and reference potential.

2.2 Electromagnetic Interference (EMI)

In environments with:

Large VFDs

High-power motors

Welding machines

Switching power supplies

analog signals often experience continuous noise coupling — not enough to fail, but enough to create unstable small fluctuations.

Typical trend:

Tiny saw-tooth noise, micro-oscillations, or non-smooth curves.

Around 40% of drift issues are related to EMI.

2.3 Cable and Terminal Problems

This is extremely common in older plants:

Moisture inside cables

Oxidized terminals

Broken shielding

Increased impedance

Aging insulation

Any of these can cause gradual signal attenuation or instability.

2.4 Transmitter’s Natural Drift

Sensors such as:

Pressure transmitters (diffused silicon)

RTDs

Thermocouples

Level transmitters

Flow transmitters

all exhibit natural drift due to:

Temperature variation

Membrane stress

Material aging

Mechanical fatigue

All transmitters drift — the only difference is how fast.

This is not a quality issue; it is physics.

2.5 Loose Terminals

One of the simplest yet most frequently overlooked causes.

Vibration-prone areas such as:

Pump rooms

Compressor rooms

Blower areas

can cause terminal screws to loosen over time.

2.6 Unstable 24 VDC Power Supply

An underrated root cause.

Ripple, load fluctuation, voltage drop, or shared grounding can all introduce drift into analog loops.

In many cases where no other cause is found, engineers finally replace the power supply — and the drift disappears.

2.7 Temperature Effects

Temperature changes affect:

Sensor sensitivity

Cable resistance

Transmitter internal electronics

Terminal contact resistance

Semiconductor characteristics

These small variations accumulate into long-term drift.

If temperature fluctuates significantly, drift becomes unavoidable without compensation and calibration.

3. How to Make the Signal Stable Again?

Despite its complexity, drift always comes down to one underlying concept:

Stability

Stable zero/reference

Stable grounding

Stable power supply

Stable cable integrity

Stable EMC environment

Stable sensor performance

Improving just one link reduces drift slightly;

improving the entire chain eliminates it structurally.

Here are the most effective engineering practices:

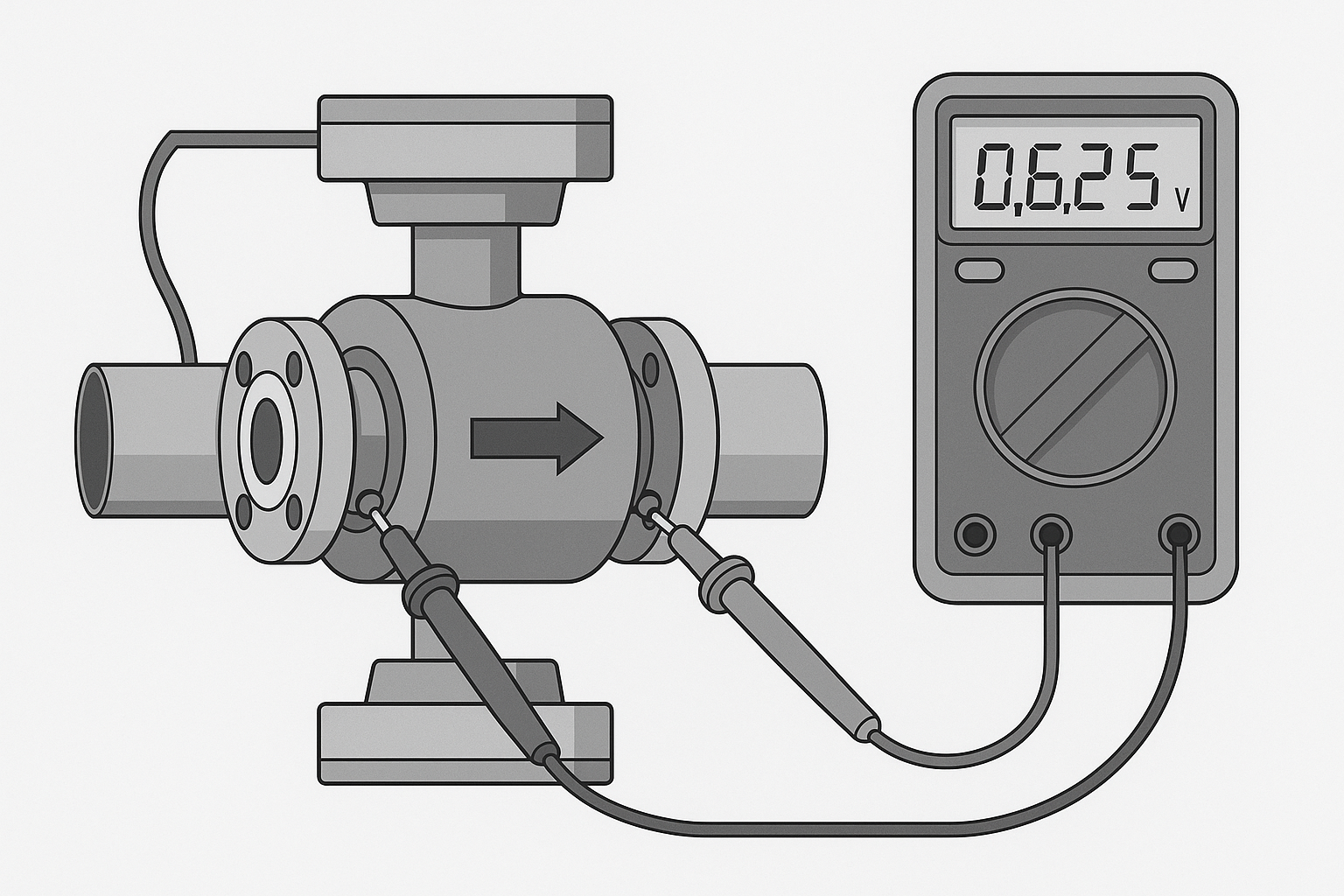

3.1 Use Signal Isolation — Stabilize the Reference

Isolation is the industry-proven method to eliminate:

Ground potential differences

EMI coupling

Multi-point grounding issues

Loop inconsistencies

In practice, 70% of drift issues can be solved by proper isolation.

3.2 Improve Wiring and EMC Design

Separate signal and power cables

Use shielded cables (shield grounded one side only)

Avoid coiling cables

Install EMC filters near VFDs

Use independent cable trays for power vs. signal

Many “mysterious” drifts are simply wiring problems.

3.3 Ensure Cable and Terminal Reliability

Use industrial-grade shielded cables

Replace aged or moisture-exposed cables

Re-tighten terminals regularly

Avoid water ingress in junction boxes

3.4 Ensure Power Supply Quality

High-quality 24 VDC supply is essential.

Symptoms of poor power:

Trend shifts with load change

Multiple loops drifting simultaneously

Values unstable during startup

3.5 Calibrate Instruments Regularly

Drift is a natural process.

Only calibration can bring the measurement back to its designed accuracy.

Critical sensors (pressure, temperature, level) should have annual or semi-annual calibration plans.

3.6 Tighten Every Terminal Screw

Simple but crucial.

Loose terminals account for a surprisingly high percentage of random drift cases.

4. What Does Drift Really Tell Engineers?

Drift is not a failure — it is an early warning.

It often indicates:

Grounding issues

Aging cables

Degraded EMC environment

Sensor aging

Unstable power supply

Temperature influence

Environmental changes

The older the system, the more frequent the drift.

The more stable the system, the less drift you’ll ever see.

Engineers who understand signal drift understand the health of the entire automation system.