Understanding DN, D, De and Ø in Engineering Practice

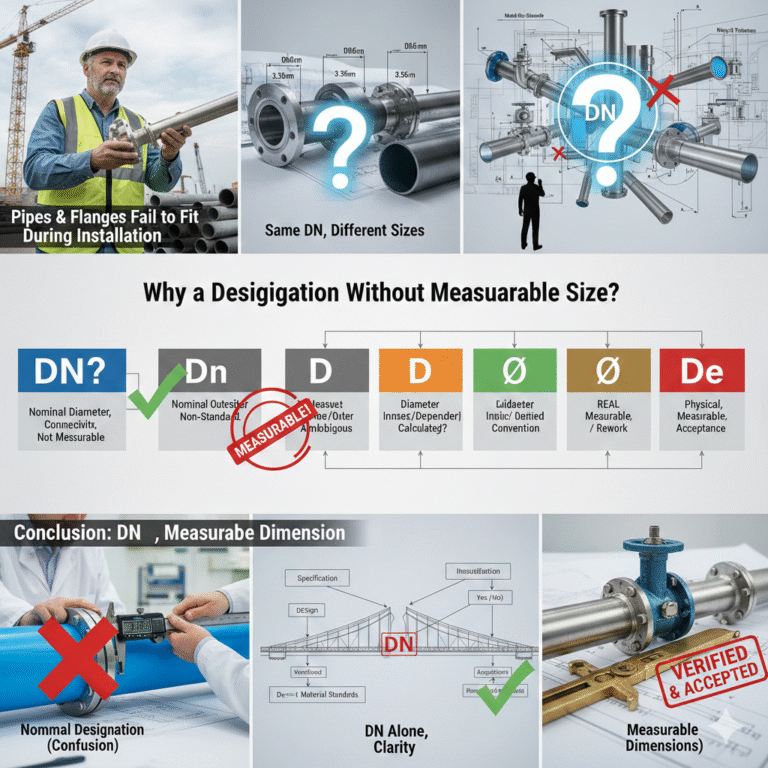

In many projects, pipes and flanges fail to fit during installation.

This problem is often attributed to poor communication, purchasing mistakes, or site workmanship.

However, from an engineering and inspection perspective, the root cause is usually much deeper — and far less intuitive.

DN itself is not a physical dimension.

Even when DN50 is consistently specified in design, procurement, and inspection, differences in outside diameter and wall thickness can still be fully compliant with standards — and yet cause installation conflicts.

This raises a fundamental question:

Why is a designation that does not represent an actual measurable size widely used for manufacturing, inspection, and acceptance?

The answer lies in how DN was originally intended to be used — and how it is often misused in practice.

1. The True Meaning of DN

DN stands for Nominal Diameter.

Its original purpose was never to describe the real geometry of a pipe.

Instead, DN was introduced to:

Standardize interface classifications

Ensure compatibility between pipes, valves, flanges, and fittings

Allow components from the same system to connect correctly

In simple terms:

DN defines connectivity, not geometry.

DN indicates whether components can be connected within the same piping system —

not how large the pipe actually is.

Once DN is separated from:

material specification

piping standard

wall thickness series

it becomes a symbolic designation rather than a usable engineering dimension.

When DN is mistakenly treated as a real size, ambiguity is introduced at the very beginning of the project — and that ambiguity is later “corrected” on site through rework, modification, or cost overruns.

2. Why DN Alone Cannot Be Used for Manufacturing or Inspection

From an engineering control standpoint, every specification must meet one basic requirement:

It must be measurable and verifiable.

DN does not meet this requirement.

You cannot measure DN using any instrument.

What you can measure are:

outside diameter

wall thickness

ovality

concentricity

This explains a common engineering situation:

DN is identical

outside diameter differs

wall thickness differs

supports, sleeves, and mating connections do not match

Yet from a standards perspective, no party has violated any requirement.

The issue does not lie in execution —

it lies in the incorrect starting definition.

3. Understanding DN, D, Ø, and De — Their Actual Engineering Roles

Confusion does not arise because too many symbols exist,

but because symbols from different engineering layers are mixed together.

Below is a clear technical interpretation:

DN — Nominal Diameter

Standardized connection designation

Does not represent a unique inside or outside diameter

Ensures compatibility within a piping system

Not suitable for manufacturing, inspection, or acceptance

Dn — Nominal Outside Diameter (non-standard usage)

Not defined as a unified international standard

Often industry- or region-specific

Sometimes used interchangeably with DN

Lacks independent engineering clarity

D

Meaning depends entirely on context

May represent inner diameter, outer diameter, or calculated diameter

Without explicit definition, ambiguity is inevitable

Ø (Diameter symbol)

Indicates that a dimension is a diameter

Does not specify which structural layer

Commonly assumed as outside diameter, but this is convention — not a standard rule

De — Outside Diameter

Real, physical, measurable dimension

Can be verified during manufacturing and inspection

Forms the basis for acceptance criteria

Widely used in plastic piping and municipal water systems

Only De represents a true geometric dimension.

4. Engineering Control Requires Measurable Parameters

From an inspection and quality-control perspective, a specification is meaningful only if it can be:

measured

verified

accepted or rejected

DN alone fails this test.

This is why experienced engineers focus not on symbolic sizes, but on parameters that can be physically confirmed.

Once specifications are expressed using measurable dimensions, responsibility boundaries become clear — and disputes significantly decrease.

5. Conclusion

Many piping conflicts commonly attributed to “lack of experience” are in fact the inevitable result of using nominal designations as physical dimensions.

True engineering clarity does not come from using more symbols,

but from ensuring that every parameter corresponds to a real, measurable object.

When the role of DN is properly understood, many recurring pipe-size problems suddenly become straightforward — not because the system changed, but because the logic finally aligns with engineering reality.