And Why HAZOP Studies Often Fail to Prevent Accidents

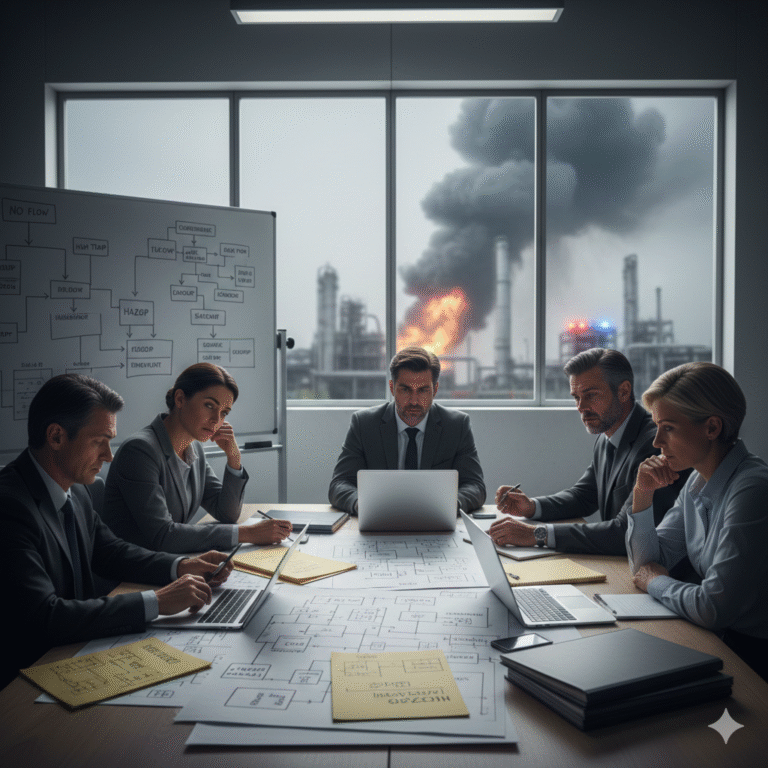

In many engineering projects, HAZOP has become a standard procedure.

The meetings are held, the worksheets are completed, reports are issued, and everything is properly archived. From a compliance perspective, nothing seems wrong.

Yet when an abnormal event or even a major accident occurs, one uncomfortable question always resurfaces:

HAZOP was conducted—so why did it fail to prevent the accident?

What frustrates many frontline engineers is that this failure is not necessarily caused by negligence.

The discussions may have been lengthy and serious. Deviations, causes, consequences, and safeguards were all documented. And yet, after start-up, problems still emerge—often in the most unexpected ways.

Over time, HAZOP gradually turns into a compliance document, rather than an engineering tool.

The true purpose of HAZOP is not to produce a report.

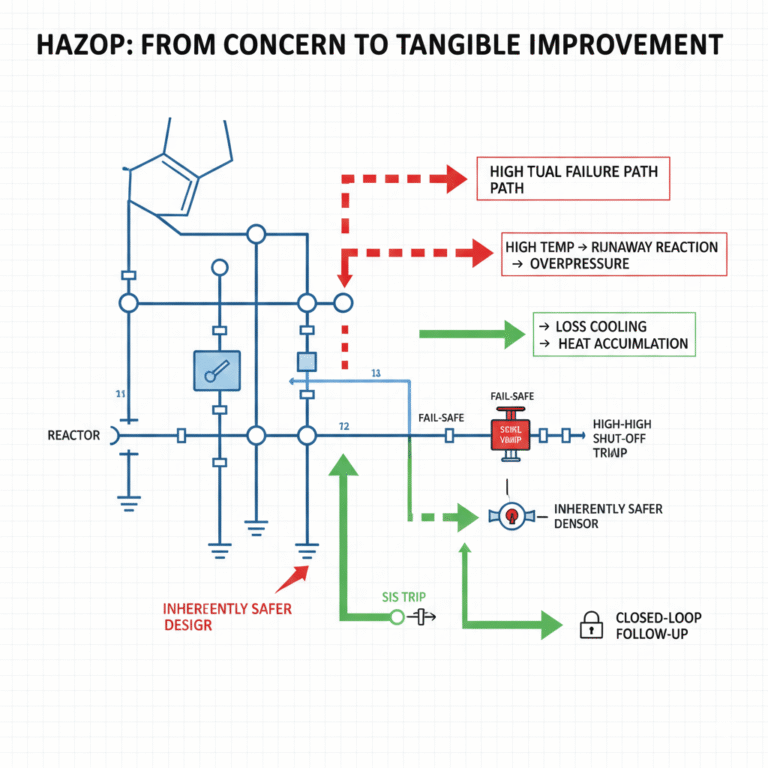

It is to identify—before an accident happens—the few critical failure paths that engineers should be genuinely concerned about, and to convert that concern into tangible improvements in design and protection.

1. What HAZOP Is Actually Doing

Accidents in complex industrial systems rarely occur suddenly.

They typically follow a recognizable path:

Assumptions made during design

Gradual deviation during operation

Failure of control or protection to interrupt the deviation

Eventual loss of control over energy or hazardous material

The role of HAZOP is to intervene between design intent and accident, systematically exposing deviations that are often assumed away, overlooked, or considered “unlikely.”

HAZOP stands for Hazard and Operability Study, a name that can easily mislead beginners into thinking it is simply a hazard checklist or an accident-prevention exercise.

In reality, HAZOP is neither accident investigation nor hazard identification, and it is certainly not a box-ticking compliance exercise.

More accurately, HAZOP is a structured engineering review method that deliberately creates deviations to test whether the design intent remains valid under abnormal conditions.

The core question of HAZOP is therefore:

When the process deviates from its design intent, can the system still be controlled, and can escalation be effectively prevented?

This is achieved by applying guide words to key process parameters at defined nodes, identifying causes, consequences, existing safeguards, and determining whether additional, traceable improvements are required.

Standards such as IEC 61882 and its national equivalents explicitly require that HAZOP outcomes support engineering decisions through documented recommendations and closed-loop follow-up—not merely completed worksheets.

Regulators increasingly focus not on whether a HAZOP was conducted, but on whether critical scenarios were truly identified and effectively controlled. This explains why accident investigations so often conclude:

Risk analysis was performed, but key hazards were inadequately identified, and safeguards were insufficient or poorly targeted.

2. Why Many HAZOP Studies Remain Superficial

The most common failure mode of HAZOP is not absence, but lack of depth.

A typical symptom is that the design intent of a node is never clearly articulated, yet the team immediately starts applying guide words. Deviations end up being recorded as generic statements such as:

High temperature

Low pressure

No flow

These statements may be formally correct, but they carry little engineering value.

What engineers truly need is clear failure paths.

Does “high temperature” result from thermal runaway, loss of cooling, or measurement bias?

Does “low pressure” indicate leakage, pump cavitation, or a transient switching condition?

If a deviation cannot be linked to a specific failure mode, discussions quickly degrade into vague causes such as “operator error” or “instrument failure,” with consequences reduced to “possible accident,” and recommendations limited to “improve training” or “enhance inspection.”

The worksheet may look complete—but the accident pathway remains poorly understood.

According to GB/T 35320 and related standards, guide words are merely discussion triggers. The real value of HAZOP lies in constructing a complete causal chain:

Deviation → Cause → Consequence → Safeguard → Recommendation

And the recommendations must be practical, verifiable, and capable of reducing risk, not generic statements.

3. Consequence Analysis Must Support Engineering Decisions

HAZOP is not a quantitative risk assessment, but consequence analysis must still reach an engineering judgment level. Otherwise, it cannot support key decisions such as:

Whether LOPA is required

Whether a SIL-rated function is justified

Whether inherently safer design changes are necessary

At a minimum, consequence analysis should clarify:

The type of energy or material released

The potential release magnitude

The affected area

The speed of escalation

Whether human intervention is realistically possible

Many scenarios evolve too rapidly or with too much uncertainty to rely on manual response. In such cases, operator action cannot be treated as a primary risk control assumption.

Regulatory scrutiny increasingly focuses on whether consequences are described in concrete, realistic operational terms. Accident reviews repeatedly show that failures are not due to lack of severity wording, but due to failure to define how severe, how fast, and how controllable the scenario truly is.

4. Safeguards Must Be Written as Reliable Barriers

Safeguards are often the most overestimated part of a HAZOP study.

Procedures, training, and inspections are necessary management measures, but they are rarely reliable, independent technical barriers.

In real accident scenarios, escalation is fast and information is incomplete. Assuming that personnel will always diagnose the situation correctly and respond in time is inherently uncertain.

Many projects only discover during LOPA or SIL analysis that their “safeguards”:

Are not independent

Are not automatic

Lack defined performance criteria

Cannot be verified through testing

At that stage, costly redesign is often unavoidable.

A safeguard should be evaluated against at least four questions:

Is it independent of the initiating cause?

Does it act automatically?

Does it have a clearly defined function and trigger condition?

Can its performance be verified through testing or inspection?

If bypasses exist, bypass management is part of safeguard effectiveness and cannot be ignored.

5. How to Perform a Meaningful HAZOP for Reactors

The depth of a reactor HAZOP lies not in listing “high” or “low” temperature, but in understanding whether heat generation can be removed, whether the system can cross safe boundaries, and whether control and protection are vulnerable to common-cause failures.

The first step is to define the design intent as verifiable boundaries, including:

Normal and maximum allowable temperature and pressure

Heat removal paths and design capacity

Key control loops and interlocks

Composition limits and safe operating envelope

Only when the intent is clear can deviations be meaningfully assessed.

Deviations should be framed as failure modes, not parameter labels.

A typical failure path is loss of cooling leading to heat accumulation—caused by insufficient cooling flow, valve sticking, fouling reducing heat transfer, or biased temperature measurement. Consequences must explicitly describe rapid pressure rise, PSV activation, material release, and escalation beyond manual control.

Another frequently overlooked path is mixing failure, leading to localized high concentrations. Bulk temperature may appear normal while hotspots trigger side reactions, polymerization, pressure spikes, or blockages.

Composition excursions due to mischarging, overdosing, or incorrect addition sequence can push heat release beyond design heat removal capacity. If these are simply attributed to “operator error,” structural risk reduction opportunities are lost.

Safeguard evaluation must focus on common-cause failure. Typical weaknesses include:

Shared sensors between control and interlock

Common power or network for DCS and SIS

Long-term bypassed interlocks still counted as protection

Relief devices not validated against runaway scenarios

Reliable protection typically includes independent high-high temperature trips that stop feed and maximize cooling, independent SIS with separate sensors, and relief systems validated for runaway conditions.

6. How to Perform HAZOP for Tank Farms

A tank farm HAZOP must go beyond stating “used for storage.”

Design intent must include operational modes and boundaries:

Product properties and hazards

Receiving, transfer, and tank-switching operations

Level, pressure, and vacuum limits

Breather systems, bunding, foam systems

Detection, alarm, and interlock strategies

Only then do scenarios such as overflow, overpressure due to blocked breathing, vacuum collapse, air ingress, and vapor accumulation naturally emerge.

A high-level deviation should be written as an overflow failure mode, not simply “high level.”

For example:

Continuous inflow causes level to exceed the safe limit, resulting in overflow from roof fittings or manways, forming a liquid pool inside the bund and generating a large flammable vapor cloud.

Causes must be system-level:

Level instrument failure or miscalibration

Incorrect tank switching logic

Disabled or bypassed high-high level interlock

Pump failing to stop

Shift handover communication gaps

Consequences must extend to vapor cloud formation, ignition sources, and toxic exposure where applicable.

Pressure deviations must clearly explain breathing system failures, such as blocked vents or flame arresters leading to overpressure, roof damage, and major releases. Vacuum scenarios are equally critical, including tank collapse or air ingress forming explosive mixtures.

For tank farms, the key question is whether high-high level protection can truly stop the transfer. An alarm is not a barrier. Effective protection usually requires an independent LSHH that stops pumps and closes fail-safe isolation valves, with regular proof testing. Bunds mitigate consequences but require strict drain management. Gas detection is a detection layer unless directly linked to automatic isolation.

7. Conclusion

The value of HAZOP does not lie in completed worksheets, but in clear understanding of critical failure paths and implementation of verifiable risk reduction measures.

A simple engineering test of a successful HAZOP is this:

After the study, were a small number of critical nodes and failure paths clearly identified, and did they lead to tangible changes in control boundaries, interlock strategies, or inherently safer design?

If not, the analysis has likely remained a formality rather than a true engineering safeguard.