In industrial manufacturing, fasteners are often categorized as standard or general-purpose components. Common fasteners include bolts, nuts, screws, washers, pins, and rivets, and they seem simple enough to procure based on specifications and install according to design. However, in modern industrial engineering systems, fasteners are far more than mere connecting parts. They are subject to strict standards, directly affect equipment safety, and are foundational structural elements built on well-defined engineering assumptions.

Numerous operational and failure cases indicate that fastener connection problems rarely stem from insufficient material “strength.” Instead, they more often arise from inadequate understanding or improper implementation of engineering standards, resulting in systemic risks. To truly understand fasteners, it is essential to shift the focus from individual parts to a systems and standards-based perspective.

The Essence of Fastener Connections

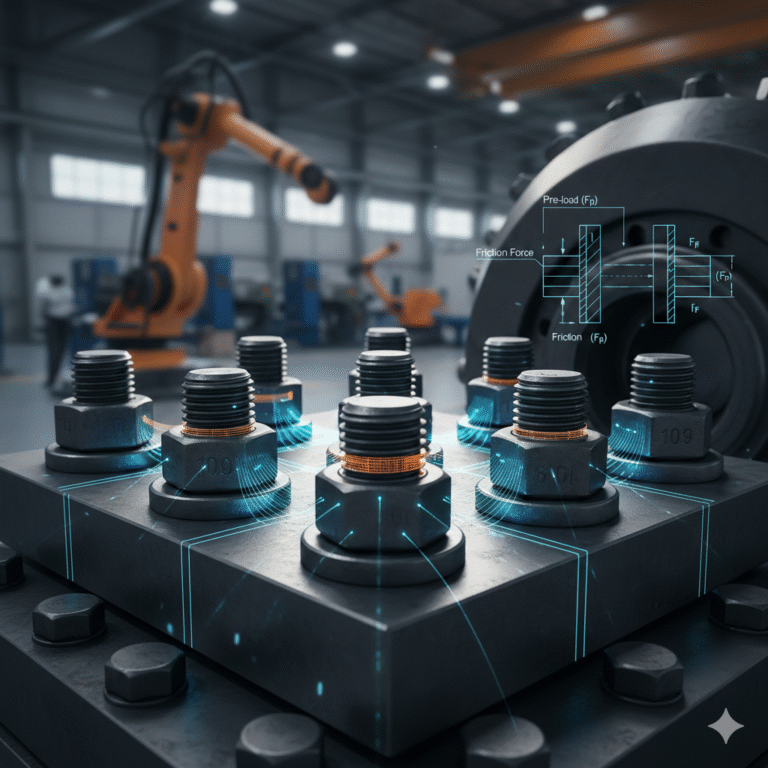

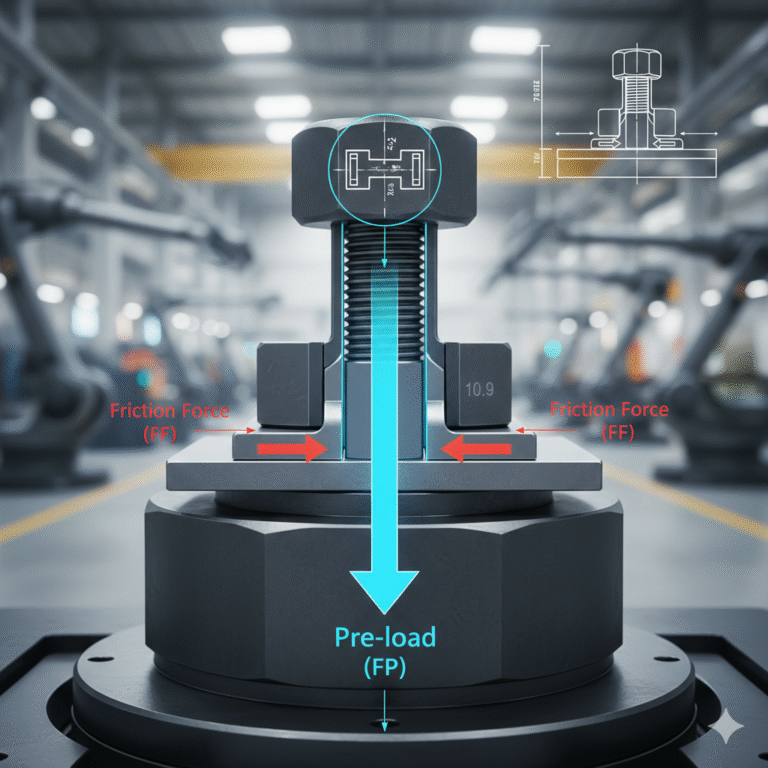

From an engineering mechanics viewpoint, a bolt connection in industrial equipment does not rely solely on the bolt itself to resist shear forces for structural stability. Instead, it relies on the axial pre-load generated during tightening, which creates a stable friction system between the connected parts.

Under ideal conditions:

External loads are primarily carried by the friction between connection surfaces, while the bolt itself mainly undergoes a stable tensile stress.

This working state is the default assumption in most industrial standards. Therefore, the reliability of fastener connections is not based on how tightly bolts are fastened, but rather on whether the pre-load is within a reasonable range and can remain stable throughout the service life.

In both domestic and international standard systems, fasteners are defined as components used to securely connect two or more parts and allow disassembly when necessary. Common foundational standards include:

GB/T 3098 Series: Mechanical properties of fasteners

GB/T 5780 / 5782: Hexagonal bolts

GB/T 6170 / 6175: Hexagonal nuts

GB/T 93 / 97: Elastic washers and flat washers

International counterparts include ISO 898, ISO 4014, ISO 4032, etc.

The core objective of these standards is not to standardize appearance, but to constrain material properties, mechanical performance, and dimensional tolerances, ensuring that fasteners behave predictably and verifiably in engineering calculations.

Pre-load in Fasteners

Pre-load is not a parameter that can be arbitrarily set; it is closely linked to loading conditions, friction characteristics, and safety factors.

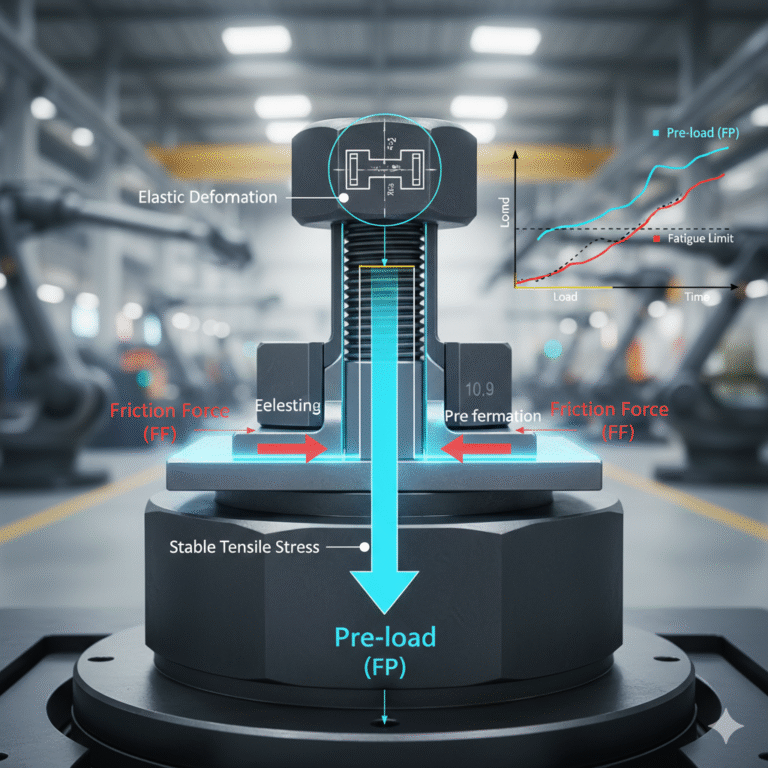

In engineering design, reasonable pre-load must meet three basic requirements:

The connection surfaces must not slip under the maximum operating load.

The bolt should always work within the elastic deformation range.

The connection system must have sufficient fatigue life.

Whether under GB or ISO standards, the fundamental engineering assumptions are consistent:

Fastener connections rely on the frictional force generated by pre-load to transfer loads.

Bolts should not serve as primary shear components.

Most failures stem from pre-load decay rather than instantaneous overload.

Insufficient pre-load can cause slight slipping of connection surfaces, gradually subjecting the bolts to alternating stresses, while excessive pre-load may result in bolt yielding, thread damage, or the crushing of connected parts. Therefore, the “safety” of fasteners is not a simple function of material strength but the result of the combined action of pre-load, friction conditions, and load spectra.

Strength Grades of Fasteners

The strength grade system of fasteners provides clear mechanical boundaries for engineering design. For example, common bolt grades include 8.8, 10.9, and 12.9 (GB/T 3098.1 / ISO 898-1):

Grade 8.8: Tensile strength ≥ 800 MPa, Yield strength ≥ 640 MPa

Grade 10.9: Tensile strength ≥ 1000 MPa, Yield strength ≥ 900 MPa

Grade 12.9: Tensile strength ≥ 1200 MPa, Yield strength ≥ 1080 MPa

Higher strength grades allow for greater working stresses but come with reduced ductility reserves. The choice of fastener grade must consider tightening processes, friction conditions, and stress concentration control. In equipment exposed to vibration, impact, or fluctuating loads, blindly opting for higher grades could accelerate fatigue failure. A reasonable selection should be based on actual load characteristics and engineering calculations rather than pursuing the “highest grade.”

Fatigue Failure

According to ISO, DIN, and high-reliability industry standards (e.g., aviation, wind power), the overwhelming majority of fastener failures are due to fatigue, not static load failure.

The typical formation path of fatigue failure is:

Initial pre-load is insufficient, or it gradually decays.

The connection surfaces undergo slight slippage.

The bolt transitions from a stable tensile state to an alternating stress state, with stress concentrations at the root of the threads, initiating micro-cracks that expand, leading to fatigue fracture.

Thus, preventing fatigue failure is not about increasing “hardness,” but about maintaining stable pre-load conditions. This is why, in critical equipment, there are restrictions on the number of times bolts can be disassembled, key bolts are prohibited from being reused, and tightening sequence and methods are strictly regulated.

Material Selection

In the fastener standard system, material selection emphasizes matching the service environment.

Carbon steel and alloy steel fasteners: High strength, good fatigue performance, and corrosion resistance are enhanced through surface treatment. Suitable for dry or mildly corrosive environments.

Stainless steel fasteners (GB/T 3098): Excellent corrosion resistance but typically lower strength compared to high-strength alloy steels.

Ignoring material mechanical properties could weaken connection reliability, particularly in high-load environments. Material selection must consider mechanical performance, environmental conditions, and service life.

Surface Treatment

The surface treatment of fasteners not only determines their corrosion resistance but also significantly alters the friction coefficient of the threads and bearing surfaces.

Since most of the tightening torque is consumed by friction, even small changes in friction coefficients can lead to significant deviations in pre-load. Therefore, standard practices often require high-strength bolts to undergo specific surface treatments, with corresponding tightening procedures and surface conditions. For example, Dacromet coatings are widely used on high-strength bolts, not because they are “more rust-resistant,” but because their friction coefficients are stable and reproducible, which helps maintain pre-load control.

Anti-loosening Design

The engineering objective of anti-loosening design is not just to prevent nuts from rotating but to delay or suppress the decay of pre-load. In environments subject to continuous vibration or impact, traditional spring washers are no longer sufficient to meet reliability requirements and are increasingly being replaced by more systematic solutions. These include structural designs that prevent relative rotation, material or geometric methods to maintain pre-load, or processes and maintenance practices to reduce decay rates.

Anti-loosening design is not about adding “extra parts” but rather a part of the overall connection system.

Fastener Lifecycle Management

In high-reliability industries such as wind power, rail transit, aviation, and nuclear power, fasteners have long been incorporated into equipment reliability engineering systems.

Design phase: Perform load and fatigue calculations according to standards.

Manufacturing phase: Control materials, heat treatment, and surface treatment.

Assembly phase: Strictly follow tightening procedures.

Operation phase: Periodically inspect key connections.

Maintenance phase: Standardize replacement and traceability management.

Fasteners are engineering units with a service life, not consumables.

Conclusion

The performance limit of industrial equipment depends on both design level and manufacturing capabilities. However, the reliability threshold is almost entirely determined by whether the most fundamental connection systems are properly understood and implemented. While fasteners may seem ordinary, they carry the most genuine and long-term engineering challenges for equipment. Respecting fasteners is fundamentally about respecting engineering principles and industrial experience.