1. Role of Surface Roughness in Flange Sealing

Surface roughness of the flange sealing face is a critical factor in ensuring a leak-tight connection.

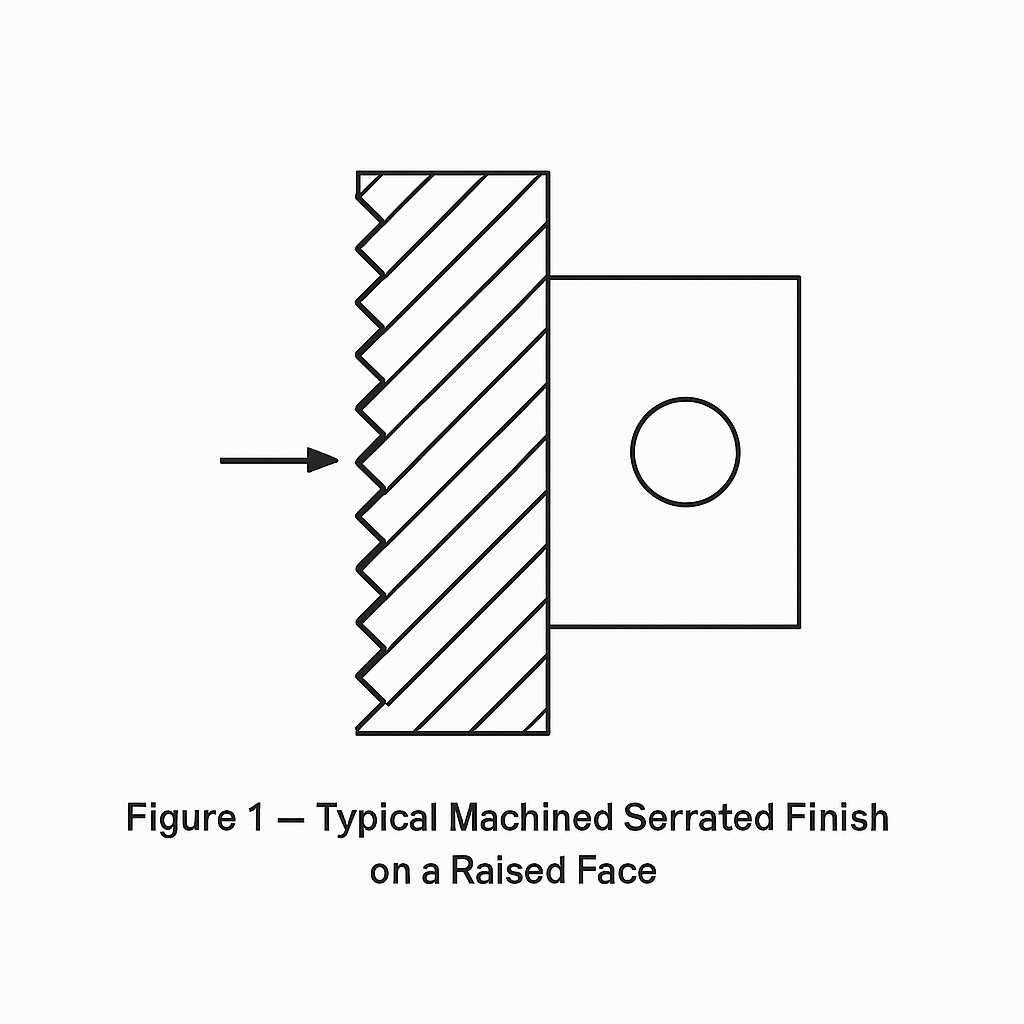

A controlled “serrated” finish enables the gasket to undergo plastic deformation and interlock with the flange surface.

Proper roughness creates sufficient frictional resistance to prevent gasket blow-out under internal pressure.

The microscopic grooves provide flow-blocking barriers, forming an effective seal.

2. Typical Roughness Values

The most common requirement for flange sealing face roughness falls within:

Ra 3.2 μm – 12.5 μm

(equivalent to ▽3 ~ ▽5 in older GB standards)

Such surfaces appear with uniform machining marks (tooling or spiral grooves) but feel smooth to the touch.

3. Differences Between Sealing Face Types

| Sealing Face Type | Typical Roughness (Ra, μm) | Application & Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Raised Face (RF), Flat Face (FF) | 3.2 – 6.3 | Common in general process piping; slightly rough surfaces increase gasket grip. Too smooth (<1.6 μm) may cause slippage. |

| Ring Joint (RJ) | 1.6 – 3.2 | High-pressure, high-temperature services; requires precise flatness for metallic ring gaskets. |

| Tongue & Groove (T/G), Male & Female (M/F) | Similar to RF | Provide gasket confinement; roughness helps soft gaskets (non-asbestos, PTFE) achieve tight sealing. |

4. Key Principle — “Not the Smoother, the Better”

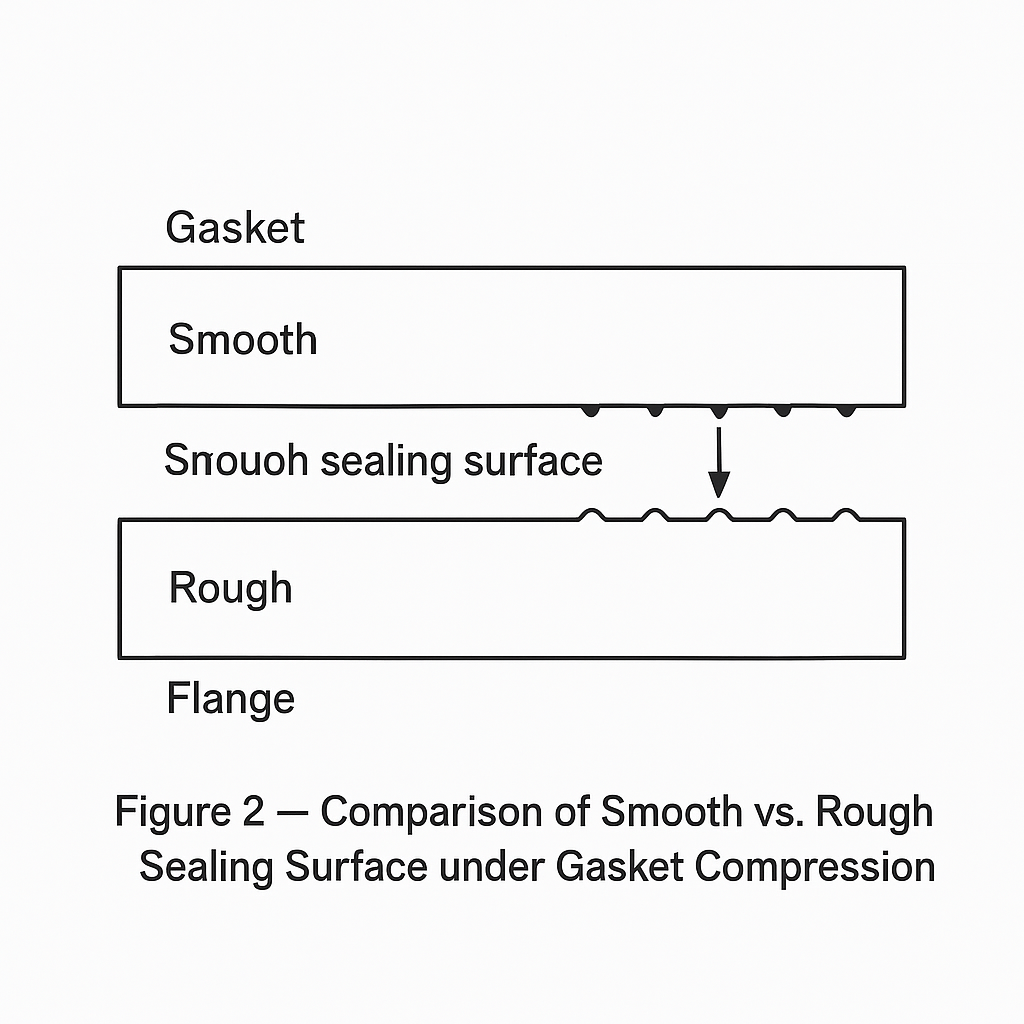

A mirror-like finish is not desirable:

Overly smooth faces reduce friction, causing the gasket to slip during bolt tightening or be extruded under fluid pressure.

Controlled roughness is essential to maintain both sealing integrity and mechanical stability.

5. Machining Methods

Turning (Lathe Cutting): Produces concentric spiral serrations. The groove orientation is perpendicular to potential leakage paths, improving sealing reliability.

Grinding/Polishing: Used for tighter tolerance requirements, especially for RJ faces.

6. Material & Gasket Compatibility

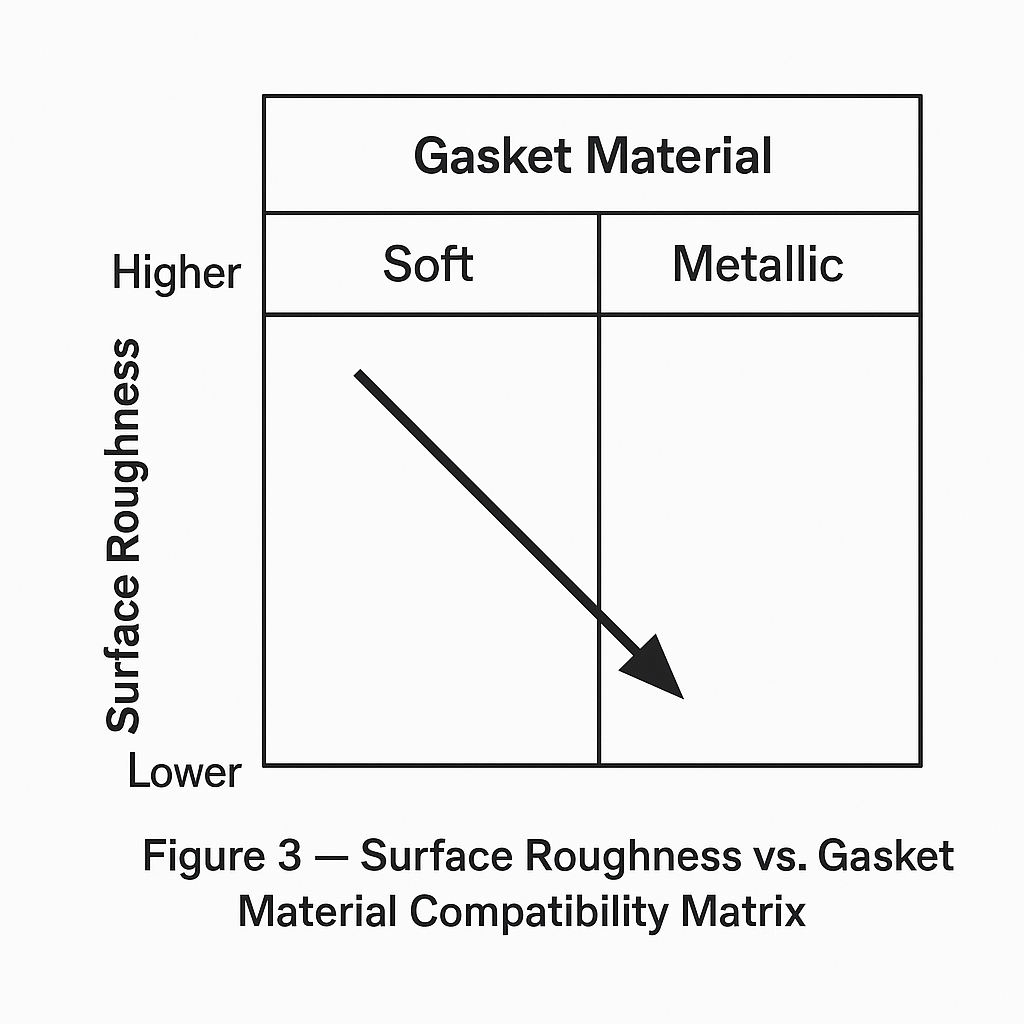

The ideal surface finish depends on the gasket material:

Soft gaskets (e.g., non-asbestos, graphite, PTFE): Require relatively rough surfaces for better mechanical interlock.

Metallic gaskets (e.g., spiral wound, ring joint): Need smoother surfaces and higher flatness to ensure precision seating.

7. Conclusion

The ideal flange sealing face is not a polished mirror, but a controlled micro-rough surface.

Roughness must be tailored to the gasket material, pressure level, and sealing face design.

A balance of frictional grip, gasket flow, and precision alignment forms the foundation of a reliable, leak-free flange connection system.