Precision instrumentation is an integral part of modern technology, spanning industries such as aerospace, healthcare, and manufacturing. The performance of these instruments relies heavily on the materials used in their construction, which must exhibit optimal combinations of hardness, strength, and stiffness. These mechanical properties determine the instruments’ durability, accuracy, and reliability under various conditions. Let’s delve into these properties and their implications for material selection in precision instrumentation.

1. Hardness: Surface Durability in Precision Parts

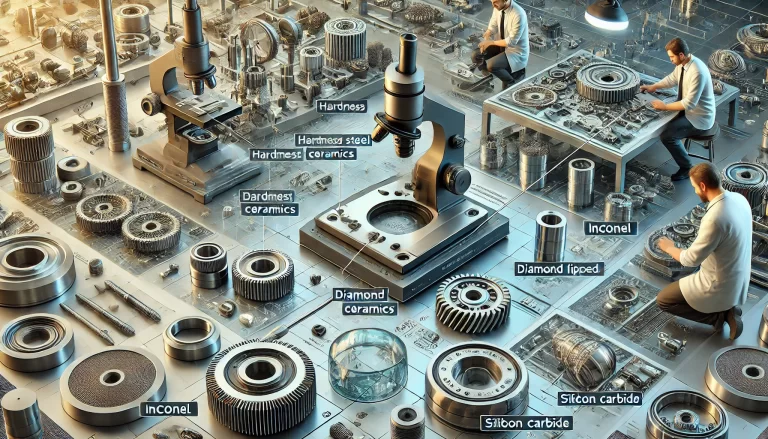

Hardness measures a material’s resistance to localized deformation, such as indentations, scratches, or wear. In precision instrumentation, components often encounter repetitive contact, sliding, or abrasion. Hardness is crucial for parts that require wear resistance and surface integrity, such as:

Bearings and bushings: High-hardness materials like hardened steel or ceramic ensure minimal wear during rotation or sliding.

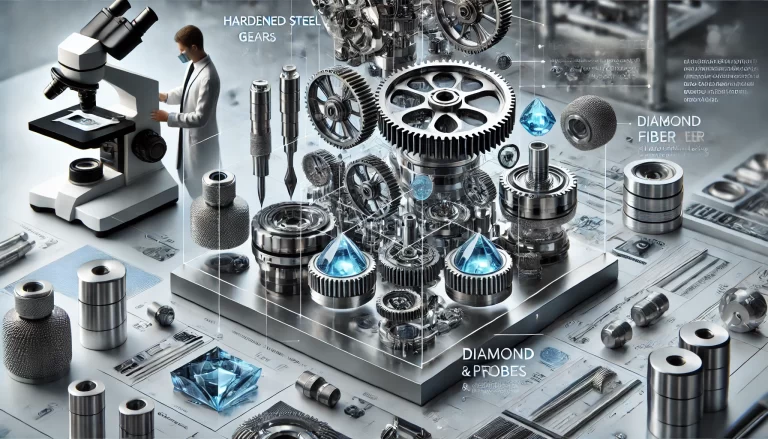

Gears: Precision-machined gears made of hardened steel (e.g., AISI 52100) resist pitting and maintain surface accuracy under prolonged use.

Measuring probes and tips: Diamond or tungsten carbide tips exhibit exceptional hardness, maintaining their sharpness and precision over time.

Common Materials:

Metals: Tool steels, hardened stainless steels, and titanium alloys.

Ceramics: Alumina (Al₂O₃), zirconia (ZrO₂), and silicon carbide (SiC).

Composites: Cermets, combining metal and ceramic properties for enhanced hardness and toughness.

2. Strength: Withstanding Operational Loads

Strength defines a material’s ability to resist deformation or fracture under applied loads. Precision instruments often face static or dynamic stresses, requiring materials with high tensile, compressive, or shear strength to maintain performance without failure.

Applications in Precision Instrumentation:

Load-bearing frames and structures: These components, often made of high-strength alloys like Inconel or 7075 aluminum, ensure mechanical stability while minimizing deformation.

Fasteners and joints: Bolts and screws in precision instruments require materials with high tensile strength to secure assemblies without loosening under stress.

Pressure vessels and chambers: Materials like stainless steel (e.g., 316L) or titanium are chosen for their ability to withstand high internal pressures without yielding.

Common Materials:

Metals: High-strength steels, aluminum alloys, and nickel-based superalloys.

Polymers: Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) for lightweight, high-strength applications.

Composites: Carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRP) for strength-to-weight advantages.

3. Stiffness: Ensuring Dimensional Stability

Stiffness, quantified by a material’s elastic modulus, represents its resistance to elastic deformation. Precision instruments demand materials with high stiffness to maintain dimensional stability and accurate performance under load. Flexing or bending of components can lead to measurement errors or mechanical failures.

Applications in Precision Instrumentation:

Optical systems: Components like lens mounts or telescope frames, often made of Invar (a low-expansion alloy) or Zerodur glass ceramic, must resist deformation to maintain alignment.

Machine tool bases: Cast iron or granite provides high stiffness and damping capacity, reducing vibrations that could affect machining accuracy.

Precision positioning stages: Aluminum or carbon fiber structures ensure lightweight yet stiff solutions for high-speed motion control.

Common Materials:

Metals: Beryllium and magnesium for high stiffness-to-weight ratios.

Ceramics: Silicon carbide for exceptional stiffness and thermal stability.

Composites: CFRP for customized stiffness properties along specific axes.

4. Balancing Properties for Optimal Performance

While hardness, strength, and stiffness are distinct properties, they often overlap in influencing material performance. In precision instrumentation, achieving a balance among these properties is critical:

Trade-offs: Increasing hardness often reduces toughness, making materials more brittle. Similarly, optimizing for stiffness may lead to increased weight, which is undesirable in portable instruments.

Hybrid materials: Combining materials, such as metal-ceramic composites or multilayer coatings, allows engineers to tailor properties to specific needs.

Surface treatments: Techniques like carburizing, nitriding, or PVD coatings enhance surface hardness while preserving core toughness and strength.

5. Advances in Material Science for Precision Applications

Recent advancements in materials science have introduced novel solutions to address the demands of precision instrumentation:

Additive manufacturing: Enables complex geometries with tailored mechanical properties, such as lattice structures for optimized stiffness and weight.

Nanostructured materials: Offer superior hardness and strength, with applications in wear-resistant coatings and high-precision components.

Smart materials: Shape memory alloys and piezoelectric materials enable active adjustments to maintain precision under varying conditions.

Conclusion

In precision instrumentation, selecting the right materials is as much an art as it is a science. Engineers must consider the interplay of hardness, strength, and stiffness to design components that deliver consistent performance under stringent demands. Advances in material science continue to push the boundaries of what is possible, enabling ever more precise and reliable instruments that support innovation across industries.