Choosing the right flow meter is not easy. It requires familiarity with both flow meter technology and the characteristics of the fluid being measured, as well as economic factors. The selection can be summarized into five key aspects: performance requirements, fluid characteristics, installation requirements, environmental conditions, and cost. None of these aspects can be ignored. Let’s take a closer look at each one!

1. Performance Requirements and Instrument Specifications

When selecting a flow meter, several performance factors need to be considered, such as whether you need to measure instantaneous flow or total (cumulative) flow, accuracy, repeatability, linearity, flow range, pressure loss, output signal characteristics, and response time. Different measurement objectives will have different priorities regarding instrument performance.

Measurement of Flow or Total Volume

There are two main measurement objectives: measuring flow rate and measuring total volume. In continuous pipeline production or process control environments, instantaneous flow is mainly measured; for batch production or commercial transactions and storage distribution, total volume is usually required, sometimes supplemented by flow rate. Depending on these two distinct functions, the measurement method will have different focus areas.

Some meters, such as volumetric and turbine flow meters, directly measure total volume with high accuracy, making them suitable for total volume measurement. Electromagnetic, ultrasonic, and differential pressure flow meters, on the other hand, measure fluid velocity to derive flow, providing quick response for process control. However, if integrated with totalizing functions, they can also provide total volume measurement.

Accuracy

How accurate does the measurement need to be? Should the meter be accurate at a specific flow rate, or across a range? How long can the chosen meter maintain this accuracy? Can it be recalibrated easily? Does it allow for in-situ verification of accuracy? These are critical considerations.

For applications involving flow control systems, the overall system’s control accuracy dictates the required accuracy of the flow meter. If the system includes errors from signal transmission, control adjustments, and other influencing factors (like actuator backlash), setting the flow meter’s accuracy too high might be unreasonable or uneconomical.

Repeatability

Repeatability is critical in process control applications and is determined by the instrument’s design and manufacturing quality. Accuracy depends not only on repeatability but also on calibration systems. In practice, instrument repeatability can be affected by fluid properties, such as viscosity and density changes.

Linearity

Flow meters typically produce either linear or square-root nonlinear outputs. The nonlinearity is often included in the overall error, but for meters used in totalizing applications over a wide range of flow, linearity is important for maintaining accuracy across the range.

Maximum Flow

Maximum flow, also known as full-scale flow, is important in selecting the correct meter size. The meter’s diameter should match the pipe’s flow range, not merely the pipe’s nominal diameter.

Flow Range

The flow range is the ratio of maximum to minimum flow rates. Linear meters generally have wider flow ranges, while nonlinear meters have narrower ranges, which might still meet most process control needs. However, some applications, such as utility water measurements, demand wider flow ranges due to varying seasonal and daily flow rates.

Pressure Loss

Most flow meters, except for obstructionless sensors like electromagnetic or ultrasonic meters, create some pressure loss due to their design. Excessive pressure loss can affect process efficiency, especially for large pipelines.

Output Signal Characteristics

Flow meters may output signals representing flow (volumetric or mass), total volume, average velocity, or point velocity. Some output analog signals (current or voltage), while others produce pulse signals. The choice depends on whether the output needs to support process control or precise flow measurements.

Response Time

In fluctuating flow environments, the meter’s response to changes in flow needs to be considered. Some meters must follow flow changes closely, while others need only provide averaged outputs.

Maintainability

When the operational conditions deviate significantly from the design or when the instrument fails, the ability to maintain and repair the meter on-site is critical. For example, differential pressure meters are highly reliable due to their design.

2. Fluid Characteristics

Fluid Temperature and Pressure

The working temperature and pressure of the fluid must be defined. This is especially important when measuring gases, as temperature and pressure can cause significant density changes, which may require adjustments to the measurement method. If changes in temperature or pressure lead to significant variations in flow characteristics, temperature and/or pressure corrections should be applied.

Density

For most liquid applications, the density is relatively stable, and correction is usually unnecessary unless there are significant density changes. For gases, the range and linearity of some meters depend on density. Low-density gases can pose challenges for certain measurement methods, such as those using mechanical elements (e.g., turbines).

Viscosity and Lubrication

Some instruments are affected by the Reynolds number, which is related to viscosity. It is important to understand the temperature-viscosity relationship when evaluating an instrument’s suitability. For gases, viscosity is generally low and doesn’t vary significantly with temperature and pressure, except for hydrogen gas.

Chemical Corrosion and Scaling

The chemical properties of the fluid may be a decisive factor in selecting a measurement method and instrument. If the fluid corrodes the instrument or causes surface scaling or crystallization, it can impact performance and reduce the instrument’s lifespan. To address these issues, manufacturers may offer specialized products such as corrosion-resistant models or those with anti-scaling measures.

Compressibility Factor and Other Parameters

When measuring gases, it’s necessary to know the compressibility factor to determine the density at working conditions. If the gas composition changes or the working conditions are near the supercritical point, it’s best to measure density online.

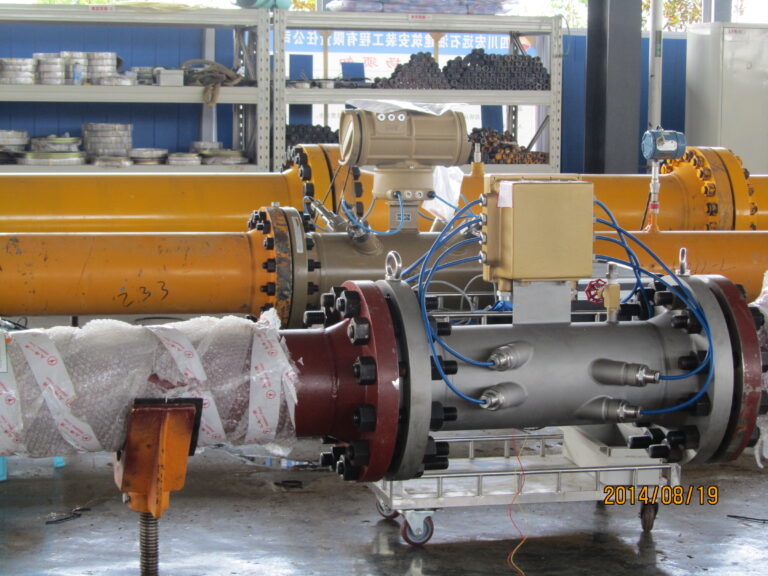

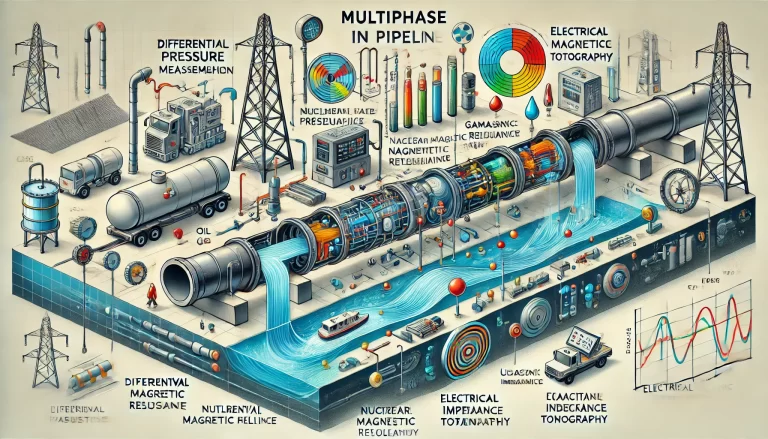

Multiphase and Multicomponent Flow

Measuring multiphase or multicomponent fluids should be approached with caution. Experience shows that general-purpose flow meters will experience changes (or significant deviations) in measurement performance when used in multiphase or multicomponent flow.

3. Installation Requirements

Different measurement methods have different installation requirements, such as upstream straight pipe length. Differential pressure and vortex meters require longer straight pipe sections, while volumetric meters and float meters may have fewer or no such requirements.

Pipeline Layout and Meter Orientation

The installation orientation (horizontal or vertical) can affect the performance of some meters. In slurry flows, solid particles may settle in horizontal pipelines.

Flow Direction

Some flow meters can only work in one direction, and reverse flow could damage the meter. If reverse flow is possible, consider installing a check valve to protect the meter.

Upstream and Downstream Pipeline Engineering

Flow disturbances from upstream pipeline configurations or flow restrictors can impact the meter’s performance. Disturbances like vortices from elbow pipes or flow velocity distortions from valves can be mitigated by adding straight pipe sections or flow conditioners.

Pipe Diameter

If the meter’s diameter range is limited, reducing or enlarging the pipe diameter to match the meter may be necessary.

Maintenance Space

Adequate maintenance space around the meter is essential to allow for repairs or replacements.

Pipeline Vibration

Meters like vortex or Coriolis mass flow meters may be sensitive to vibration and should be installed with supports to minimize interference.

Valve Position

Control valves should be installed downstream of the flow meter to avoid issues like cavitation or distorted flow distribution.

Electrical Connections and Electromagnetic Interference

Electrical connections must have protection against interference from stray electrical fields. Signal cables should be kept away from power cables to reduce electromagnetic or radio-frequency interference.

Protective Accessories

Some flow meters may require accessories to ensure proper operation, such as trace heating to prevent fluid condensation or alarms for partially filled pipes.

4. Environmental Conditions

Ambient Temperature

Excessive ambient temperatures can affect the meter’s electronic components, changing its performance. In such cases, the meter might need an environmental enclosure.

Humidity

High humidity accelerates corrosion and reduces electrical insulation, while low humidity increases the likelihood of static discharge.

Safety

In explosive environments, select meters that meet the relevant safety standards, such as explosion-proof designs.

Electromagnetic Interference Environment

Consider interference from high-power motors, switching devices, relays, welding machines, broadcast and TV transmitters, etc.

5. Economic Considerations

When considering economic factors, it’s important not only to account for the meter’s purchase price but also other costs such as accessories, installation, maintenance, calibration, operating expenses, and spare parts.

Installation Costs

Installation costs should include auxiliary items such as bypass pipes and shut-off valves for regular maintenance.

Operating Costs

Operating costs include energy consumption during operation, such as electricity for electronic meters or gas for pneumatic instruments. Pumping costs, due to pressure loss, are a hidden expense that is often overlooked.

Calibration Costs

Regular calibration costs depend on the calibration frequency and the required accuracy of the instrument. For petroleum storage and trade settlement applications, standard volume calibration systems are often installed on-site.

Maintenance Costs

Maintenance costs include labor and spare parts needed to keep the system running smoothly after it is in use.