A Practical Guide to Flow Measurement and Flowmeter Selection

Introduction

Why does an electromagnetic flowmeter become less accurate when measuring sludge-containing wastewater?

Why does a steam flow measurement still fluctuate badly even when an imported differential pressure transmitter is installed?

Why does an oval gear flowmeter measuring lubricating oil seize after only a few months of operation?

In many industrial applications, flow measurement problems are not caused by the brand or quality of the instrument itself, but by a misunderstanding of flow characteristics and application conditions.

This article provides a practical explanation of key flow concepts—single-phase vs. multiphase flow, laminar vs. turbulent flow, and Reynolds number—and explains how they directly affect flowmeter selection and long-term measurement reliability.

1. Single-Phase Flow vs. Multiphase Flow

Definitions

Single-phase flow:

The fluid consists of only one physical phase, such as clean water, pure steam, or refined oil.Multiphase flow:

The fluid contains more than one phase, such as liquid with solid particles, liquid with gas bubbles, or slurry.

Practical Implications

In industrial sites, multiphase flow is far more common than expected. Examples include:

Wastewater containing sand or sludge

Process liquids with entrained gas

Oil mixed with impurities or particles

Many flow measurement failures occur when instruments designed for clean, single-phase fluids are applied to multiphase conditions.

Engineering guidance:

Avoid positive displacement meters (e.g. oval gear meters) in fluids containing solids.

For abrasive or slurry applications, non-intrusive or full-bore meters such as electromagnetic flowmeters with PTFE lining are generally more robust.

2. Laminar Flow vs. Turbulent Flow

Flow Regimes

Laminar flow:

Fluid moves in smooth, parallel layers with minimal mixing. Velocity distribution is stable and orderly.Turbulent flow:

Fluid motion is chaotic, with strong mixing, eddies, and velocity fluctuations.

In practical terms:

Laminar flow typically occurs at low velocity, high viscosity, or small pipe diameters.

Turbulent flow occurs at higher velocities and in most industrial pipelines.

Why This Matters

Many flowmeters are calibrated and optimized under turbulent flow conditions.

Operating them in laminar or transitional flow can lead to:

Reduced accuracy

Poor repeatability

Increased sensitivity to installation conditions

3. Reynolds Number (Re)

Definition

The Reynolds number is a dimensionless parameter representing the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces in a flowing fluid.

Typical interpretation:

Re < 2000 → Laminar flow

Re > 4000 → Turbulent flow

2000 < Re < 4000 → Transitional (unstable and unpredictable)

Practical Meaning for Engineers

Reynolds number is not just a theoretical concept—it directly affects:

Flow profile stability

Flowmeter accuracy

Suitability of different measurement technologies

Example:

Electromagnetic and vortex flowmeters generally perform best at high Reynolds numbers (fully turbulent flow).

Variable area (rotameter) flowmeters can operate reliably at low Reynolds numbers.

Ignoring Reynolds number during selection is a common reason for poor field performance.

4. Overview of Common Flowmeter Technologies

4.1 Differential Pressure Flowmeters

Differential pressure flowmeters measure flow based on the pressure drop across a primary element (orifice plate, nozzle, Venturi).

Key characteristics:

Flow rate is proportional to the square root of differential pressure.

Highly sensitive to fluid density, pressure, and temperature.

Engineering considerations:

Steam and gas applications require pressure and temperature compensation.

Poor compensation is a major cause of unstable or drifting measurements.

4.2 Oval Gear Flowmeters

Oval gear flowmeters are positive displacement meters suitable for clean, viscous liquids.

Advantages:

High accuracy for oils and fuels

Good performance at low flow rates

Limitations:

Extremely sensitive to solid particles

Not suitable for dirty or contaminated fluids

4.3 Variable Area (Rotameter) Flowmeters

Rotameters measure flow based on the equilibrium position of a float in a tapered tube.

Best suited for:

Low flow rates

Low Reynolds number applications

Visual indication and simple systems

4.4 Electromagnetic Flowmeters

Electromagnetic flowmeters operate based on Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction.

Key requirements:

Fluid must be electrically conductive

Pipe must be completely full

Strengths:

No obstruction in the flow

Excellent for wastewater, slurry, and corrosive liquids

Minimal pressure loss

4.5 Vortex (Vortex Shedding) Flowmeters

Vortex flowmeters measure flow by detecting vortices generated behind a bluff body.

Typical applications:

Steam

Gas

Clean liquids

Important notes:

Requires sufficiently high Reynolds number

Sensitive to vibration and installation conditions

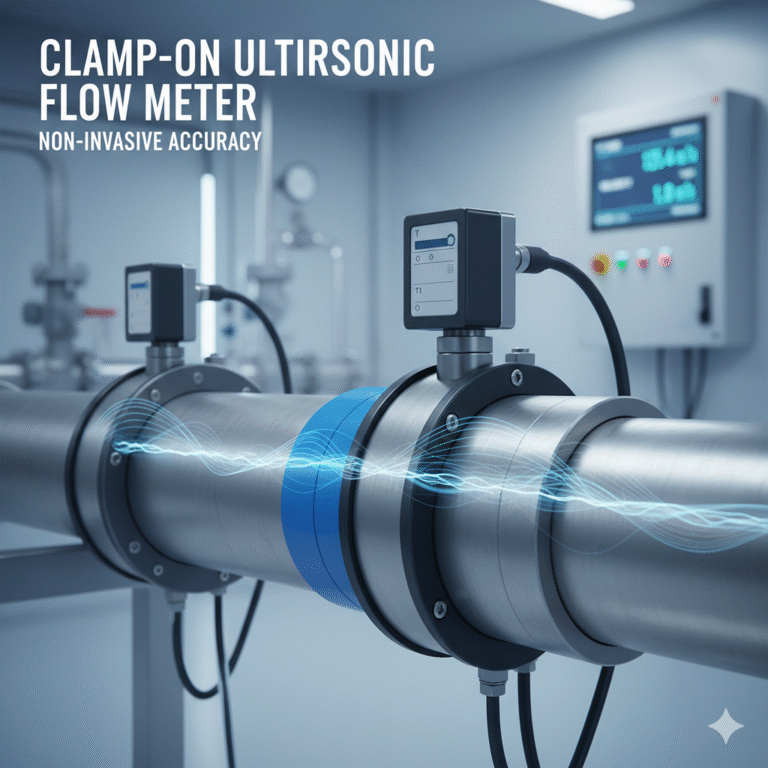

4.6 Ultrasonic Flowmeters

Ultrasonic flowmeters measure flow by analyzing the interaction between ultrasonic signals and the flowing fluid.

Main types:

Transit-time: for clean liquids

Doppler: for fluids containing particles or bubbles

4.7 Coriolis Mass Flowmeters

Coriolis flowmeters directly measure mass flow based on tube vibration and Coriolis force.

Advantages:

Direct mass flow measurement

High accuracy

Independent of flow profile

Considerations:

Higher cost

Sensitive to external vibration in some installations

5. Key Takeaways for Flowmeter Selection

From a practical engineering perspective:

Always identify whether the fluid is single-phase or multiphase

Check whether the operating Reynolds number ensures stable flow conditions

Match the flowmeter principle to fluid properties, not brand preference

For steam and gas, never ignore pressure and temperature compensation

A correct selection at the design stage prevents most long-term measurement problems

Conclusion

Accurate flow measurement is not achieved by selecting the most expensive instrument, but by selecting the most suitable technology for the actual process conditions.

Understanding flow behavior is the foundation of reliable measurement—and the key to avoiding costly field issues later.