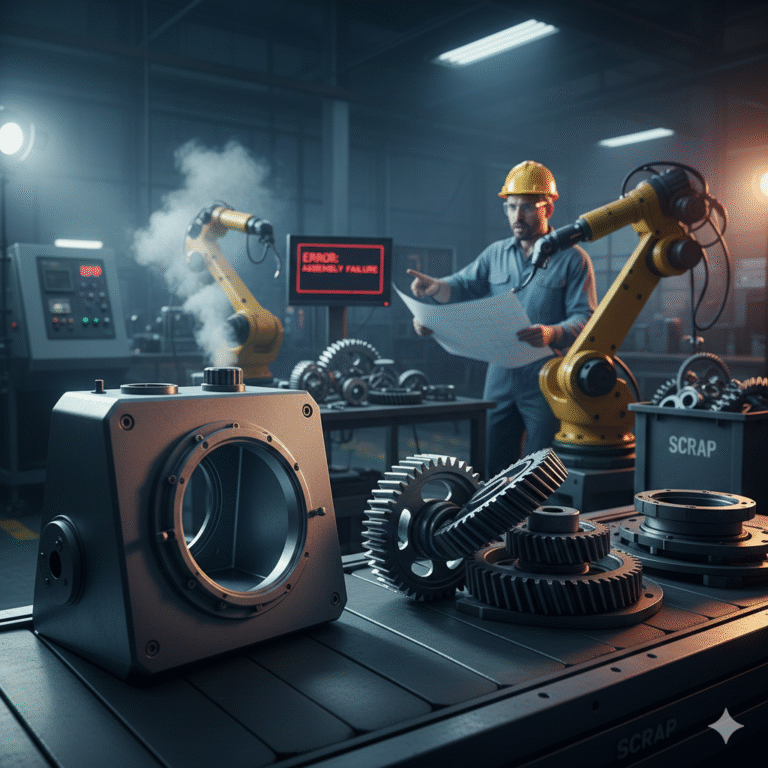

In manufacturing, many visible issues appear at the final stage—parts don’t fit, assemblies generate noise, performance fluctuates, or costs spiral.

However, when engineers trace the root cause, they often discover that these problems arise much earlier—during the design phase—where tolerance selection and accuracy requirements were already misaligned.

Tolerance grades and accuracy levels are fundamental to every engineer, yet surprisingly misunderstood.

Many designers recognize IT6, IT7, and IT8, but few understand why those grades exist, which applications they are intended for, and which shouldn’t be applied casually in routine design.

To use tolerances effectively, engineers must step back from intuition and examine the intersection of standards, real-world manufacturing capability, and functional requirements.

1️⃣ The Essence of Tolerance

From a standards perspective, tolerance is not guesswork—it is a precise, quantified specification.

According to GB/T 1800.1—2020 / ISO 286, tolerance is:

“The difference between the permissible maximum and minimum limit of a size.”

This definition reveals three critical points:

Tolerance defines the acceptable dimensional variation given by design—not by manufacturing.

Tolerance only determines acceptance or rejection—whether a part is in or out of spec.

Tolerance does not describe manufacturing capability—it is a design boundary, not a machine performance indicator.

This is why ISO 286 offers twenty tolerance grades, from IT01 through IT18, covering everything from metrology standards to coarse structures.

2️⃣ The Layered Logic Behind IT Grades

The long list of IT grades often gives the wrong impression—complex, confusing, hard to apply.

In reality, each grade naturally corresponds to a level of engineering requirement and manufacturing difficulty:

| Grade Range | Engineering Category | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| IT01–IT2 | Ultra-precision | Metrology references, calibration masters |

| IT3–IT4 | High-specialty precision | Optical systems, scientific instruments |

| IT5–IT7 | Precision engineering | Critical fits, motion interfaces, alignment |

| IT8–IT9 | General engineering | Standard fits, structural features |

| IT10–IT12 | Looser dimensions | Non-critical geometry, installation space |

| IT13–IT18 | Rough tolerance | Castings, weldments, sheet metal envelopes |

In real product design, most parts rely on only five to six grades—not all twenty.

3️⃣ Tolerance vs Accuracy — The Most Common Confusion

Tolerance belongs to design.

Accuracy belongs to manufacturing.

Tolerance defines the allowed dimensional envelope.

Accuracy describes where the actual results fall inside that envelope.

A mature manufacturing system may achieve extremely tight distribution within an IT7 tolerance band—this is high accuracy, even though the tolerance is not small.

Therefore:

Tight tolerance does not automatically mean high accuracy

High accuracy does not require extreme tolerances

4️⃣ Tighter Tolerance ≠ Better Engineering

A well-balanced design aligns tolerance with function, assembly, and cost, rather than defaulting to tighter values.

✔ Function First

If a dimension affects fit, sealing, motion, or lifetime → use IT5–IT7.

If the dimension simply defines space or form → IT8–IT10 is typically sufficient.

Over-tolerancing wastes resources without increasing performance.

✔ Assembly-Driven

Alignment holes, dowel locations, and reference datums often require higher consistency—not for precision, but to:

avoid over-constraint,

improve buildability,

reduce assembly failures.

In these cases, IT6 or IT7 is usually adequate.

✔ Cost Awareness

Tolerance is a cost amplifier:

IT8 → IT7: noticeable cost increase

IT7 → IT6: often 2× or higher

IT6 → IT5: exponentially harder, riskier, and more expensive

A smart design:

Uses the widest tolerance that still meets function.

Then relies on process control—not shrinking tolerances—to maintain long-term accuracy.

5️⃣ The Role of Tolerance in Quality Management

Even with all parts within IT7 limits, persistent results near one tolerance edge indicate:

unstable machining,

poor process capability,

potential batch risk.

Thus:

Tolerance controls acceptance, but

Process capability (Cpk, Cp) controls predictability.

These two must work together—neither is sufficient alone.

6️⃣ Conclusion

Tolerance grades and accuracy levels are not academic concepts—they define how products behave in the real world.

A mature engineer:

understands which tolerance is required,

knows when not to tighten a tolerance,

balances functionality, manufacturability, and cost.

When this discipline is applied in the design phase, many downstream manufacturing and assembly problems simply never occur.

High engineering maturity isn’t measured by “how tight the tolerance is,”

but by “how appropriate the tolerance is.”