Making the Right Engineering Choice Beyond “Contact” and “Non-Contact”

Radar technology for level measurement is already well established in industrial applications.

In oil & gas, chemical processing, energy, and water treatment, radar level transmitters have almost become the default solution.

Yet in real projects, a recurring question remains:

If both are radar technologies, why are some applications better suited for guided wave radar, while others insist on non-contact radar level transmitters?

Explaining this choice simply as “contact vs. non-contact” is rarely sufficient for sound engineering decisions.

In reality, guided wave radar and non-contact radar are not interchangeable technologies.

They are based on different measurement assumptions, address different types of uncertainty, and therefore succeed—or fail—under different conditions.

1. Level Measurement Is Essentially About Managing Uncertainty

In industrial environments, liquid level is rarely a clean, stable geometric surface.

Every level measurement is, in essence, a negotiation with uncertainty, which mainly appears in three forms:

Interface uncertainty

Foam, emulsions, turbulence, or vague phase boundaries make the “true level” difficult to define.Propagation path uncertainty

Vapor, dust, pressure variations, and internal tank structures distort signal transmission.Sensor condition uncertainty

Condensation, buildup, crystallization, or aging alter the sensor’s operating boundary over time.

The fundamental difference between guided wave radar and non-contact radar is not which technology is more advanced, but where each technology places and manages these uncertainties.

2. Non-Contact Radar Level Transmitters

Non-contact radar transmitters emit microwave signals from an antenna toward the product surface.

The signal travels through the vapor space, reflects off the liquid surface, and returns to calculate the level.

Their strengths are well known:

Completely non-contact, avoiding corrosion, buildup, and contamination

Suitable for high temperature, high pressure, and aggressive or hygienic applications

Capable of very long measuring ranges, ideal for large tanks and vessels

No mechanical probes, eliminating risks of deformation or coating over time

For crude oil tanks, product storage tanks, and large vertical vessels, non-contact radar is often irreplaceable.

However, these advantages rely on a critical assumption:

The liquid surface must be a clearly identifiable electromagnetic target in free space.

When this assumption is compromised, challenges quickly emerge:

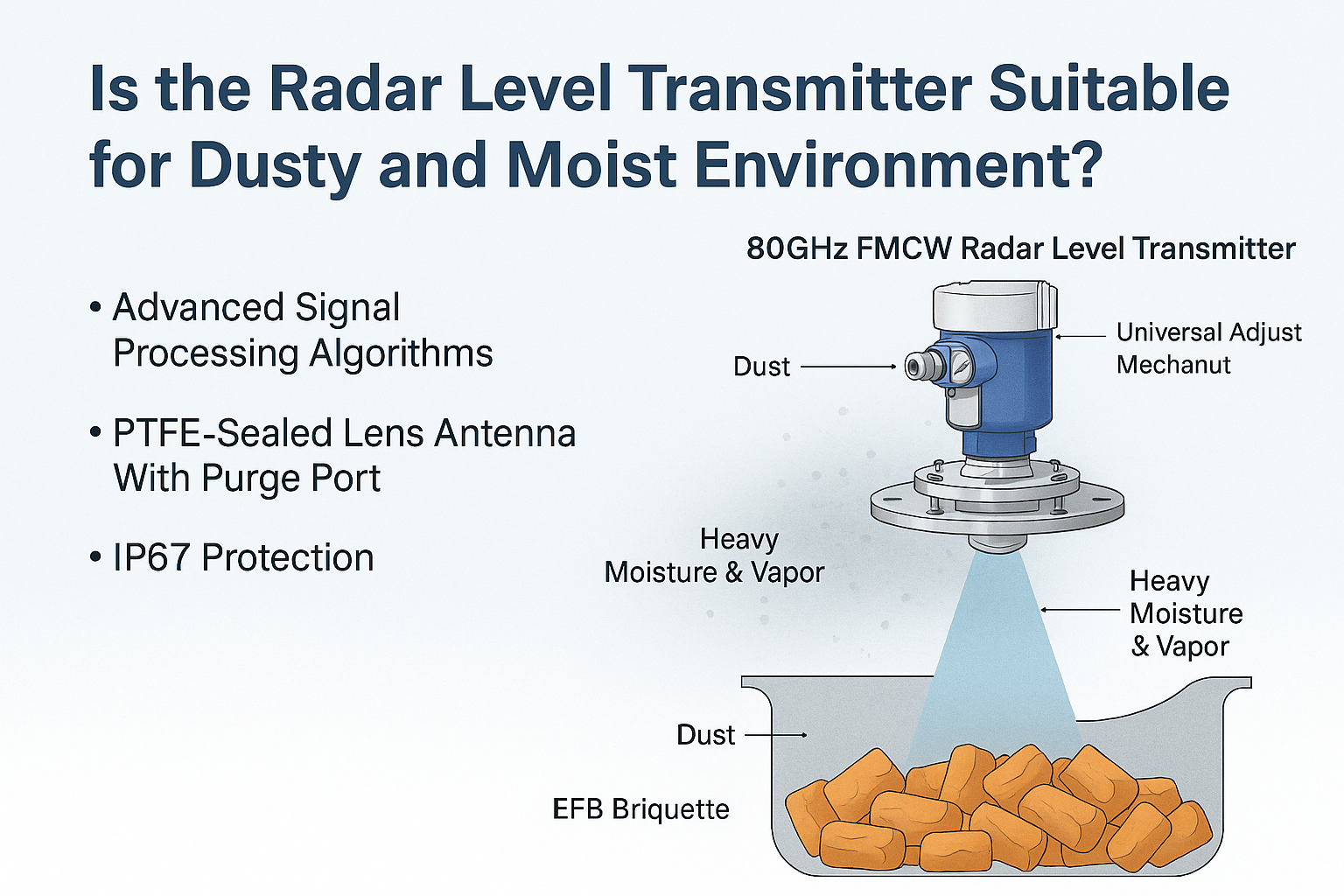

Vapor density changes cause attenuation and refraction

Foam and dust introduce scattering and false echoes

Internal structures such as agitators and coils create strong reflections

Severe surface turbulence leads to unstable echo signals

In such cases, non-contact radar does not necessarily “fail,” but it becomes highly dependent on advanced signal processing, echo evaluation strategies, and engineering experience to reliably identify the true level.

3. Guided Wave Radar Level Transmitters

Guided wave radar follows a fundamentally different measurement philosophy.

Instead of allowing electromagnetic waves to propagate freely, the signal is guided along a probe or cable, constraining the propagation path.

This design reshapes the uncertainty distribution:

Fixed signal path with minimal influence from vapor or dust

Reduced sensitivity to foam, pressure, and gas phase disturbances

Improved detectability for low dielectric constant media

More stable echo patterns, beneficial for repeatability and trend monitoring

As a result, guided wave radar often performs more reliably in applications with complex internal conditions or strong vapor interference.

This stability, however, comes at a cost.

Because the probe is in contact with the medium, guided wave radar introduces its own limitations:

Risk of buildup, crystallization, or polymerization on the probe

High-viscosity products may coat the probe and dampen reflections

Mechanical stress or turbulence can affect cable stability

Installation constraints become significant in very large tanks

In short, guided wave radar reduces spatial uncertainty, but increases dependence on sensor surface condition.

4. Dielectric Constant: Not a Simple “Measurable or Not” Parameter

In practice, dielectric constant is often treated as a binary criterion—either a medium can be measured or it cannot.

In reality, it primarily affects measurement margin and robustness.

For non-contact radar, low dielectric constant means weak reflections, which can easily be overwhelmed by vapor, foam, or internal echoes

For guided wave radar, low dielectric constant also weakens reflections, but the guided energy concentration often maintains usable signal strength

This does not mean guided wave radar is immune to dielectric effects.

Rather, the challenge is transformed into whether a stable impedance discontinuity can be formed along the probe.

5. Interface Measurement Capabilities

In applications such as oil-water separation, extraction, or settling processes, interface measurement is critical.

When the dielectric contrast between phases is sufficient, guided wave radar can generate multiple reflection points, enabling simultaneous measurement of:

Gas–liquid level

Liquid–liquid interface

However, this capability is not automatic. It depends on:

Adequate dielectric difference between phases

A stable and well-defined interface

Proper probe positioning within the interface zone

In cases of severe emulsification or unstable phase boundaries, other measurement technologies—or even non-contact radar—may be more appropriate.

6. Different Technologies, Different Interference Sensitivities

An often overlooked but essential reality is:

Non-contact radar is primarily influenced by spatial conditions

Guided wave radar is primarily influenced by sensor surface conditions

Therefore, “interference resistance” cannot be compared directly.

In reactors filled with vapor, foam, and internal structures, non-contact radar echo evaluation becomes increasingly complex.

In contrast, in sticky, crystallizing, or polymerizing media, guided wave radar may introduce long-term maintenance challenges.

7. Conclusion: Engineering Selection Is About Failure Modes

From a lifecycle perspective, neither technology is universally superior:

Non-contact radar excels in clean, large-scale applications where non-contact measurement and long-term reliability are critical

Guided wave radar performs better where spatial interference is dominant and signal stability is prioritized

Ultimately, engineering selection is not about whether a device can measure today, but whether its long-term failure modes are acceptable.

When application assumptions hold, the technology performs as intended.

When they are violated, even the most advanced instrument becomes unreliable.

Understanding this distinction is far more valuable than memorizing when to “choose guided wave radar or non-contact radar.”