Vortex flowmeters are widely used for measuring both liquid water and steam in industrial applications.

Although the fundamental measuring principle remains the same, the physical properties of the media—such as density, viscosity, temperature, and pressure—lead to significant differences in installation requirements, compensation methods, and sensor selection.

This article explains the common principles and key differences between water and steam measurement using vortex flowmeters, helping engineers select and apply the instrument correctly.

1. Common Principles (Shared Fundamentals)

Despite measuring different media, vortex flowmeters operate on the same basic concepts when used for both water and steam.

1.1 Identical Measuring Principle

Vortex flowmeters are based on the Kármán vortex street principle.

When fluid flows past a bluff body (vortex shedder), alternating vortices are generated downstream. The vortex shedding frequency is proportional to the flow velocity and is used to calculate volumetric flow rate.

1.2 Similar Mechanical Structure

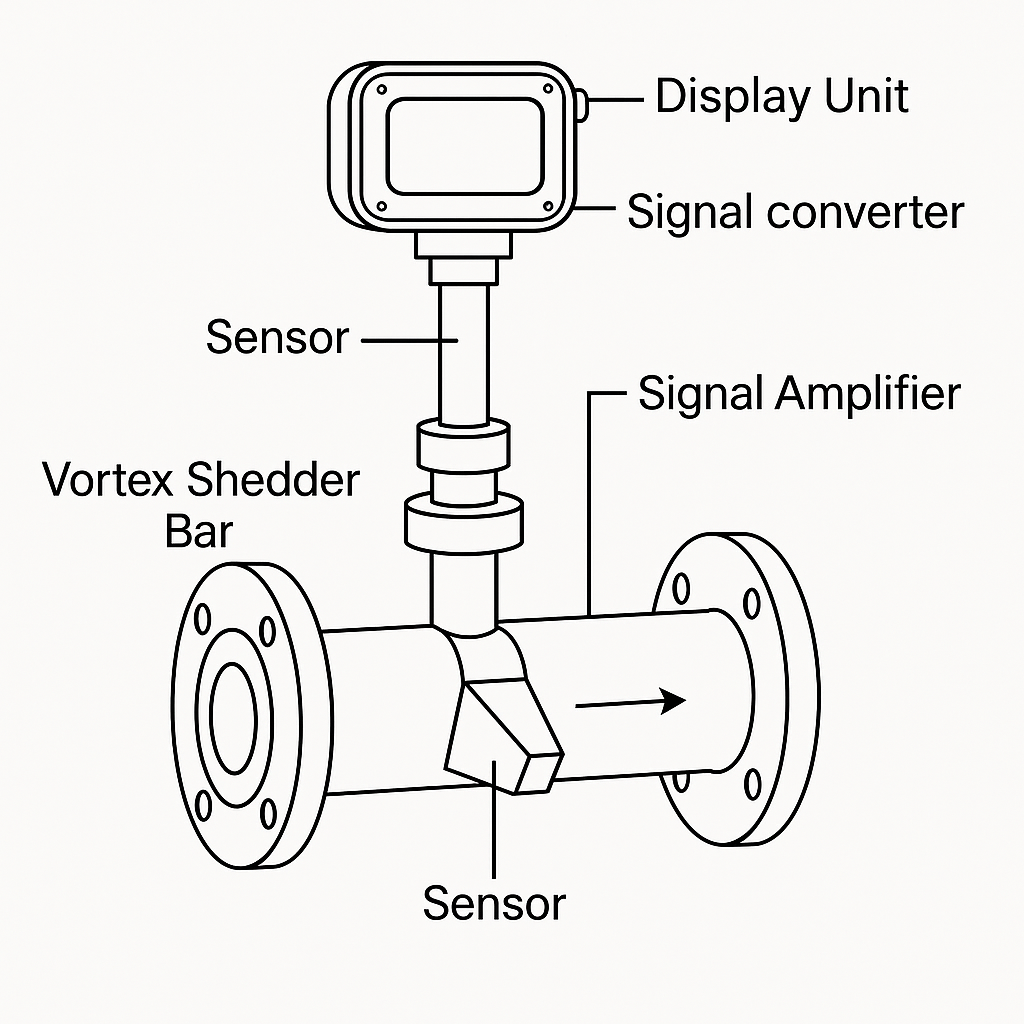

Typical vortex flowmeters for both water and steam consist of:

A vortex shedder bar

A sensing element (such as a piezoelectric or capacitive sensor)

A signal converter

In all cases, full-pipe flow is essential to ensure stable vortex generation and accurate measurement.

1.3 Unified Output Signals

Both applications support standard industrial outputs, such as:

4–20 mA analog signal

Pulse output

These signals can be used for flow indication, totalization, or integration into DCS/PLC control systems.

2. Key Differences Caused by Medium Properties

Due to the fundamental differences between liquid water and steam, their measurement characteristics vary significantly.

2.1 Medium State

Water Measurement

Typically single-phase liquid

Operates at ambient or moderate temperatures

Viscosity and density remain relatively stable

Steam Measurement

Can be saturated steam (near gas–liquid boundary) or superheated steam

Operates at high temperature and pressure

Medium state is highly sensitive to temperature and pressure fluctuations

2.2 Density and Flow Type

Water

Density is nearly constant (≈1000 kg/m³ at room temperature)

Volumetric flow is often sufficient

Mass flow calculation usually does not require additional compensation

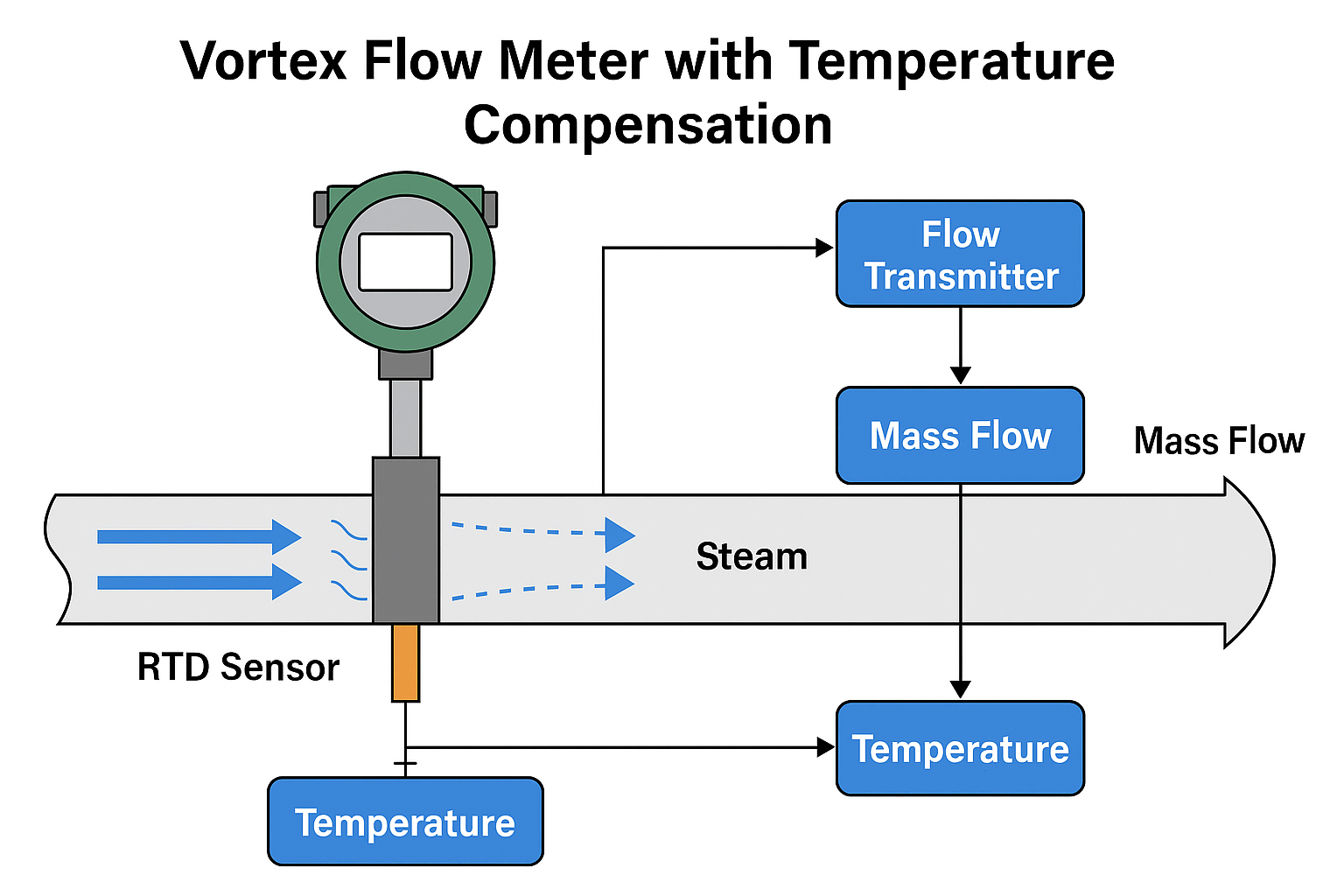

Steam

Density varies significantly with temperature and pressure

For example, saturated steam density increases from approximately 0.58 kg/m³ at 0.1 MPa to about 5.15 kg/m³ at 1 MPa

Accurate measurement requires temperature and pressure compensation to convert volumetric flow into mass flow

2.3 Sensor and Material Selection

Water Applications

Liquid viscosity has minimal impact on vortex frequency

Sensor selection mainly focuses on resistance to fouling and erosion caused by impurities

Standard piezoelectric sensors are generally sufficient

Steam Applications

Typical operating conditions:

Temperature: 150–400 °C

Pressure: 0.1–10 MPa

Sensors must withstand high temperature and pressure

Materials must resist oxidation and corrosion caused by steam

Stainless steel (e.g., 316L) and high-temperature-rated sensors are commonly required

2.4 Installation Requirements

Water Measurement

Air bubbles must be avoided, as they interfere with vortex detection and may cause over-reading

Can be installed horizontally or vertically

For vertical installation, upward flow is recommended to maintain full-pipe conditions

Steam Measurement

Liquid slugging must be strictly avoided

Saturated steam may condense due to pressure drops, forming liquid droplets

Installation is recommended at the highest point of the pipeline, where steam naturally accumulates

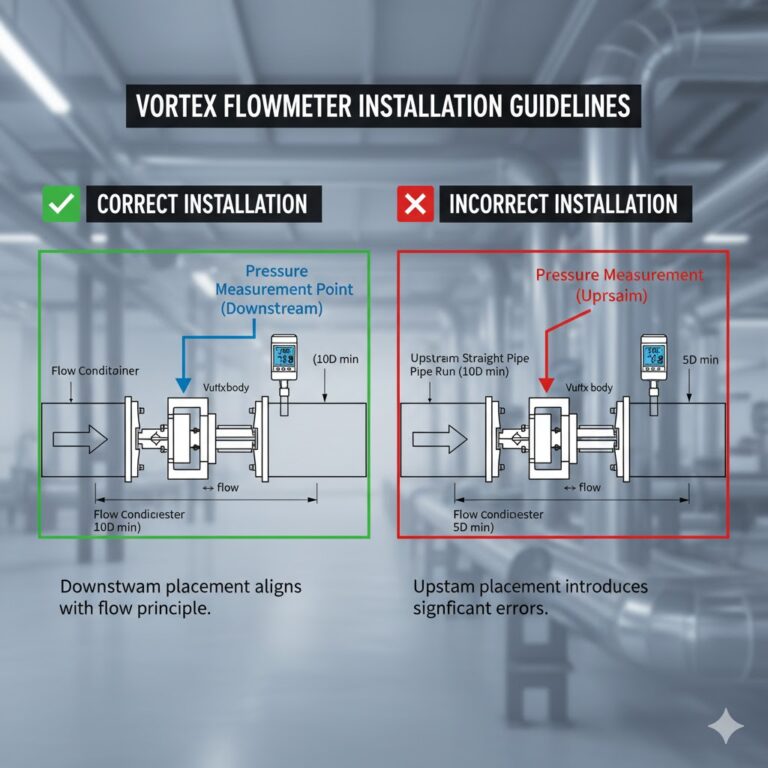

Longer straight pipe lengths are required:

Upstream: typically ≥20D

Downstream: typically ≥10D

Steam separators are often recommended for improved measurement stability

2.5 Protection and Maintenance

Water Applications

Adequate ingress protection (e.g., IP67) is required in humid environments

Periodic cleaning may be necessary to remove scale or deposits

Steam Applications

High-temperature sealing is critical (e.g., metal bellows instead of elastomer seals)

Regular inspection of temperature and pressure transmitters is essential to ensure accurate compensation

Compensation errors can directly affect mass flow accuracy

2.6 Vortex Stability and Measurement Accuracy

Water

Wide applicable flow velocity range

Stable vortex formation

Typical accuracy: ±0.5% to ±1%

Steam

High flow velocity (often 30–50 m/s)

Pressure fluctuations may cause rapid velocity changes

Vortex frequency may fluctuate more than in liquid applications

Typical accuracy: ±1% to ±2%

Signal converters with filtering functions are recommended

3. Engineering Conclusion

Vortex flowmeters operate on the same fundamental principle when measuring water and steam.

However, steam measurement places much higher demands on:

Sensor materials

Installation design

Temperature and pressure compensation

High-temperature sealing and long-term stability

Water measurement mainly focuses on avoiding air entrainment and fouling, while steam measurement requires careful control of condensation, density variation, and compensation accuracy.

In both applications, the basic conditions—full-pipe flow, stable velocity, and minimal external disturbance—are essential to ensure reliable and accurate vortex flow measurement.