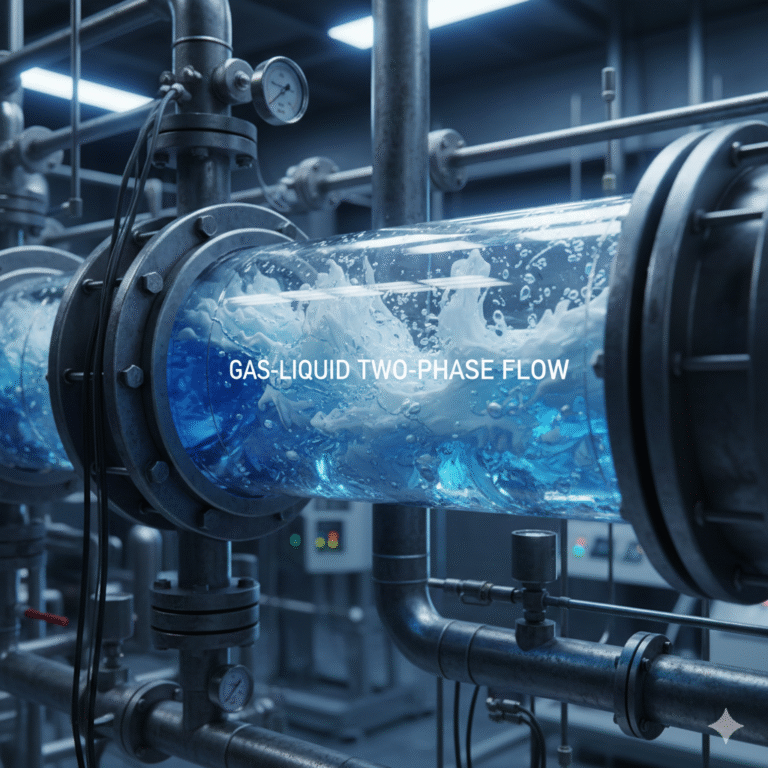

In many engineering systems, gas and liquid do not flow independently, but coexist, interact, and flow together. This phenomenon is known in fluid dynamics as gas-liquid two-phase flow.

Two-Phase Flow: Definition and Characteristics

Two-phase flow refers to the simultaneous interaction of two different phases (gas and liquid) within a pipe or conduit, resulting in unique flow behaviors and patterns. These patterns are the result of the interplay between various forces such as surface tension, gravity, and viscosity. The interaction between the two phases causes changes in the pressure and velocity of the fluid passing through the system.

Unlike single-phase flow (where only gas or liquid flows), the complexity of gas-liquid two-phase flow arises from one key element: the ever-changing interface between the gas and liquid phases. This interface is what makes two-phase flow one of the most unpredictable yet unavoidable issues in engineering systems. It affects energy consumption, heat transfer limits, equipment lifespan, and even determines whether instability or accidents will occur.

In industries such as oil and gas gathering, nuclear cooling, boiler evaporators, refrigeration systems, chemical reactors, and aerospace thermal control, the intuition from single-phase flow often fails.

Phases and Interfaces

In technical terms, a “phase” refers to a substance in a specific state (solid, liquid, or gas) with uniform thermodynamic properties, distinct from other phases. For example, the gas phase and the liquid phase.

Gas-liquid two-phase flow is not simply the simultaneous flow of gas and liquid; it involves:

Two phases with significantly different densities, viscosities, and compressibilities.

A clear but continuously changing interface between the two phases.

The position, shape, and number of these interfaces directly influence the system’s behavior.

This interface could be the outer surface of a gas bubble, a liquid film adhering to the pipe wall, or the surface of numerous high-speed moving droplets. Engineering studies on two-phase flow focus on how interfaces form, evolve, break, and disappear, as well as how they impact momentum and energy transfer.

Flow Patterns

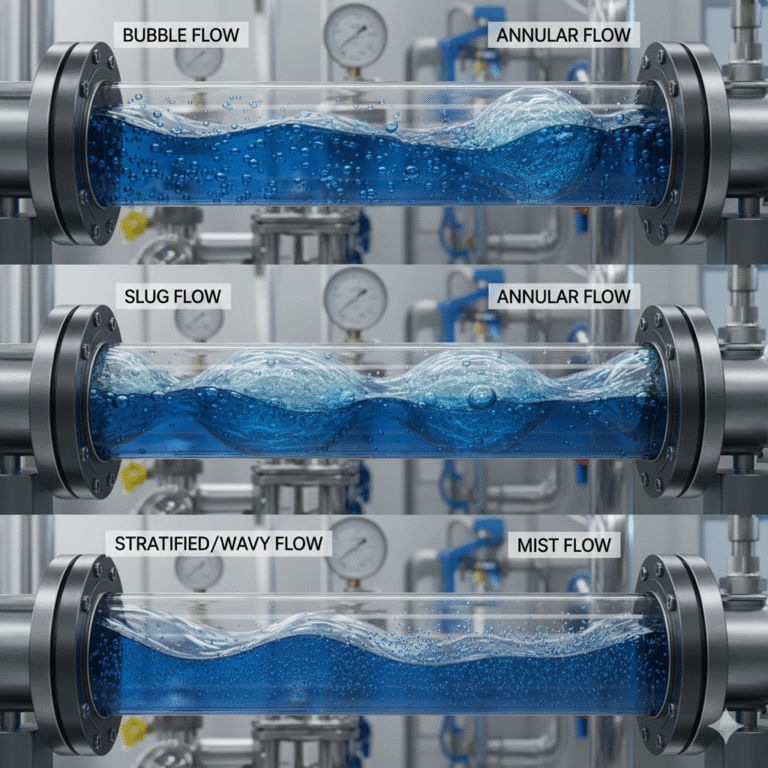

In gas-liquid two-phase flow, the distribution of the gas and liquid phases in space is referred to as the flow pattern. Flow patterns are not just descriptive phenomena; they are essential for engineering calculations. The same pipeline and operational conditions can lead to drastically different pressure drops and heat transfer rates depending on the flow pattern.

Common flow patterns include:

Bubble Flow: Gas is dispersed as small bubbles in a continuous liquid phase, typical in low gas-content conditions and often observed at the onset of boiling.

Slug Flow: Large gas bubbles and liquid slugs alternate, causing noticeable cyclic pressure and flow rate fluctuations.

Stratified/Wavy Flow: The gas and liquid phases separate due to gravity, with the interface potentially forming waves. This is common in horizontal pipes or low-flow conditions.

Annular Flow: Gas flows at high speed in the center of the pipe, with the liquid forming a film on the pipe wall. This is a critical and hazardous flow pattern in high-heat flux systems.

Mist Flow: The liquid phase is fully atomized into droplets, suspended in the gas phase, significantly reducing wall-wetting ability.

Transitions between flow patterns are often abrupt. Once the boundary between flow patterns is crossed, the system behavior can change drastically.

Void Fraction, Gas Quality, and Slip Ratio

In two-phase flow, a single “velocity” or “density” cannot describe the system. Therefore, several key physical quantities are introduced:

Void Fraction (α): This is the volume fraction of the gas phase at a given cross-section or volume. It determines the average density of the mixture and is crucial for calculating gravity-induced pressure drops and sound velocity.

Gas Quality (x): This refers to the mass fraction of the gas phase, often used in boiling and condensation analysis. For example, x = 0.2 means that 20% of the mass is in the gas phase.

Slip Ratio: This describes the ratio of the average velocities of the gas and liquid phases. Because gases are typically faster than liquids, this difference directly impacts measurement results and model accuracy.

The challenge with these quantities is that they cannot always be measured directly and must often be inferred through models.

Pressure Drop in Two-Phase Flow

The pressure drop in two-phase flow consists of three components:

Frictional Pressure Drop: Caused by the fluid’s interaction with the wall and shear between the phases.

Gravitational Pressure Drop: Determined by the mixture’s density and the height difference.

Accelerational Pressure Drop: Resulting from changes in velocity, especially noticeable during phase transitions.

Key differences in two-phase flow are:

The pipe wall is not always wetted by the liquid phase.

Phase changes alter the overall mass distribution.

Inter-phase slip introduces additional momentum exchange.

There are two common models for two-phase flow:

Homogeneous Model: Assumes equal velocities for both phases, suitable for quick estimations.

Separate Flow Model (Two-Fluid Model): Models the gas and liquid phases separately, with coupling through interfacial interactions. This model is more accurate but depends on empirical closures.

Boiling, Condensation, and Critical Heat Flux

Nucleate Boiling: Gas bubbles form on a wall surface, grow, detach, and carry heat away. This is the primary cause of efficient heat transfer. The liquid film at the base of the bubbles has extremely high evaporation rates.

Critical Heat Flux (CHF): When the heat flux density exceeds a certain threshold, the wall becomes separated from the liquid phase by steam, drastically reducing heat transfer efficiency and causing the wall temperature to spike. This is a critical issue in nuclear power, boilers, and electronic cooling systems.

Condensation: The condensation process is typically controlled by the liquid film on the wall. The thinner the liquid film, the lower the thermal resistance. High-speed gas flow can either thin the liquid film to enhance heat transfer or induce unstable oscillations.

Two-Phase Flow Instabilities

Two-phase systems are often closed-loop feedback systems with interactions between flow, phase change, pressure, and temperature. As a result, they are prone to self-excited oscillations.

Common instability forms include:

Density Wave Oscillation: Caused by heating-induced density changes, which feedback into the flow rate.

Pressure Drop Oscillation: Non-monotonic pressure drop relationships lead to multiple steady states.

Two-Phase Water Hammer: The coupling of transient phase change and pressure waves creates strong shocks.

Slug Impact: Periodic liquid slugs impact structural components, causing fatigue damage.

In many cases, two-phase flow accidents are not caused by “insufficient strength” but by a sudden shift in flow behavior.

Conclusion

Gas-liquid two-phase flow is not a subject that can be mastered through formulas alone. It is a coupling problem between fluid dynamics, heat transfer, phase change, stability, and engineering systems. For this reason, it remains irreplaceable in energy, chemical, refrigeration, nuclear, and high-end heat dissipation applications.

By understanding and controlling gas-liquid two-phase flow, we can significantly improve energy efficiency, safety, and system performance.