In engineering design and material selection, material properties directly affect product safety, lifespan, and cost control. However, in practice, some misunderstandings still persist, such as:

“A material with high strength is less likely to deform.”

“If a structure is soft, it’s due to insufficient strength.”

“A material is too brittle if it fractures.”

While these concepts may seem intuitive at first glance, they are not entirely accurate from the perspective of material mechanics principles and engineering standards, and can lead to incorrect design decisions.

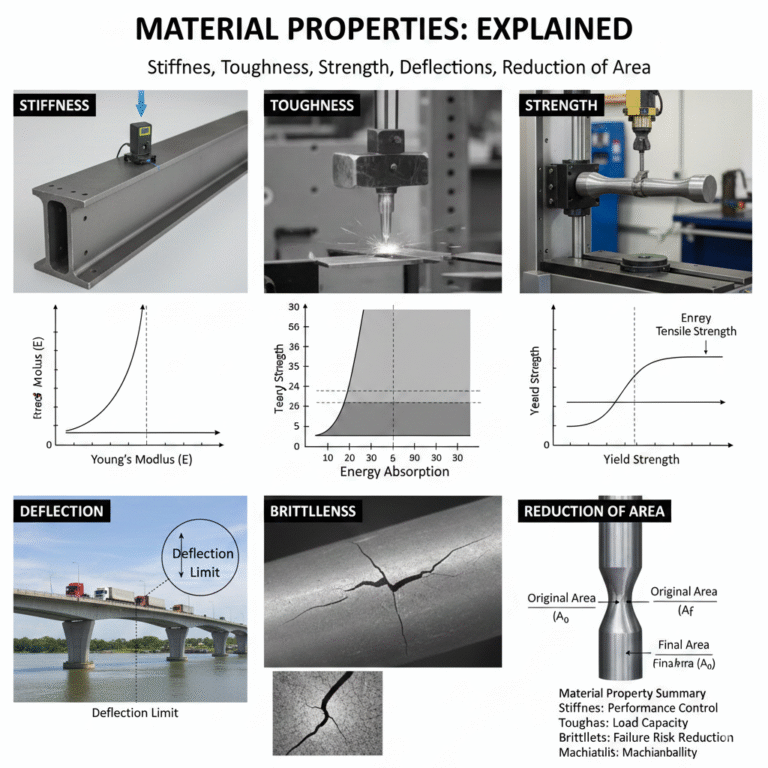

This article systematically explains the physical meanings, engineering roles, and regulatory positioning of six commonly used and often confused material properties: stiffness, toughness, strength, deflection, brittleness, and reduction of area.

It is important to note that engineering standards never rely on a single indicator to make judgments. Structural failure is often the result of multiple factors working together. These six indicators are fundamental elements of a material’s multidimensional performance system.

1. Stiffness

Stiffness refers to a material or structure’s ability to resist elastic deformation. At the material level, stiffness is primarily determined by the material’s Young’s Modulus (E), which is defined in the standard GB/T 22315 for the determination of the elastic modulus of metals. The elastic modulus does not typically change significantly with increasing material strength.

In engineering standards, stiffness is often reflected in deformation control clauses, such as:

Deflection control requirements for bridge structures

Stiffness and precision requirements for machine tools and precision equipment

Deformation limits for pipelines and support structures

These clauses focus on whether the structure can meet normal functional requirements rather than whether it will fracture.

| Material Type | Young’s Modulus (E) / GPa | Stiffness Perception |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Steel/Alloy Steel | 200–210 | Very “hard” |

| Cast Iron | 110–160 | Much lower than steel |

| Aluminum Alloy | 68–72 | About 1/3 of steel |

| Copper Alloy | 100–130 | Between steel and aluminum |

| Engineering Plastics (PA, POM) | 2–4 | Highly deformable |

2. Toughness

Toughness is the ability of a material to absorb energy through plastic deformation before fracture. In mechanics, toughness is often characterized by:

The area under the stress-strain curve

The energy absorbed in impact tests

The GB/T 229 standard outlines the use of impact absorption as a key indicator of material toughness. In engineering, toughness is important because real-world load conditions often involve rapid load changes, off-center loading, and stress concentration. Materials with certain toughness can absorb energy through plastic deformation, reducing the risk of sudden failure.

3. Strength

Strength refers to a material’s ability to resist failure or irreversible deformation when subjected to external forces. Common strength indicators in engineering include yield strength, tensile strength, compressive strength, and shear strength.

In GB/T 228.1, yield strength is used to distinguish between the elastic and plastic stages of a material, which is a critical design parameter in structural codes like GB 50017 for steel structures.

Strength indicates whether a material will fail under certain stress conditions, but not whether a structure will deform under normal usage. Many components operate well below their yield strength but may still fail due to other factors.

| Material Type | Yield Strength / MPa | Tensile Strength / MPa | Engineering Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q235 Carbon Steel | ≈235 | 370–500 | Low strength, but stable and high tolerance |

| 45# Steel (Tempered) | ≈355 | 600–800 | Balanced strength and ductility |

| Q690 High Strength Steel | ≥690 | 770–940 | High strength, sensitive to defects |

| 6061-T6 Aluminum Alloy | ≈240 | ≈290 | Strength similar to low-carbon steel, but lighter |

| HT250 Gray Cast Iron | — | ≈250 | No clear yield, brittle fracture |

4. Deflection

Deflection is not a material property, but rather the deformation of a structure under load. It is influenced by many factors such as the material’s Young’s modulus, the length and geometry of the component, load types, and boundary conditions.

In standards like GB 50010 (Concrete Structure Design Code) and GB 50017 (Steel Structure Design Code), deflection limits are often set to control:

Cracking and durability issues

Comfort and usability

Precision in equipment installation

Safety of secondary structures and attachments

Exceeding deflection limits is a common reason for design adjustments and rework.

5. Brittleness

Brittleness is a failure characteristic rather than a single performance indicator, primarily characterized by:

Very low plastic deformation ability

Sudden fracture

High sensitivity to notches and cracks

Regulatory frameworks such as GB 150 (Pressure Vessel Code) explicitly limit the use of brittle materials, setting restrictions on operating temperature ranges, thicknesses, and welding methods for components.

| Material Type | Charpy Impact Energy / J (at room temperature) | Fracture Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Low Carbon Steel | 40–100 | Clear plastic fracture |

| Low-Alloy High-Toughness Steel | 80–150 | Fully deforms before fracture |

| 6061-T6 Aluminum Alloy | 15–40 | Limited plasticity |

| Ductile Cast Iron | 10–25 | Between steel and gray cast iron |

| Gray Cast Iron | <10 | Sudden brittle fracture |

6. Reduction of Area

Reduction of area is an important indicator in tensile testing, representing a material’s local plastic deformation ability before fracture. In GB/T 228.1, it is used alongside elongation to evaluate material ductility.

From an engineering perspective, elongation reflects overall plasticity, while reduction of area gives insight into local necking and fracture behavior. This indicator is critical for assessing material suitability for machining and predicting whether deformation will occur before failure in complex stress scenarios.

| Material Type | Elongation / % | Reduction of Area / % | Plasticity Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Carbon Steel | 25–35 | 50–65 | Excellent plasticity |

| Medium Carbon Steel (Tempered) | 14–20 | 40–55 | Good plasticity |

| High Strength Steel | 10–14 | 30–45 | Limited plasticity |

| 6061-T6 Aluminum Alloy | 8–12 | 20–30 | Moderate plasticity |

| Gray Cast Iron | ≈0 | ≈0 | Almost no plasticity |

7. Role of Six Material Properties

From the perspective of engineering standards, these six properties correspond to the following control objectives:

Stiffness: Performance control in use

Toughness: Impact resistance and safety margin

Strength: Load-bearing capacity control

Deflection: Structural acceptance criteria

Brittleness: Failure risk limitation

Reduction of Area: Machining adaptability and failure prediction

Together, they form the basic framework for evaluating engineering materials.

8. Conclusion

Engineering accident analyses show that issues often arise not because materials fail to meet standards, but because their properties are not fully understood or applied. Mature engineering judgment relies not on the number of parameters but on understanding which performance indicators correspond to which risk control requirements in engineering standards. By integrating material properties, structural behavior, and regulatory logic, we can achieve safe, reasonable, and controllable engineering designs.