Limestone wet desulfurization technology has long been the mainstream in various industries, not only because the equipment is “robust” and efficient but also because it can maintain relatively stable performance under varying loads, coal qualities, and operating conditions. Engineers who only focus on surface-level processes, such as “spraying, reaction, and gypsum output,” may often be led astray by system issues. However, by mastering the underlying principles, one can effectively handle common challenges such as efficiency loss, scaling, clogging, and poor dehydration.

This article provides an in-depth explanation from several key perspectives: reaction mechanisms, liquid-gas structures, control strategies, root causes of failures, system coupling, energy utilization, and by-product crystallization control.

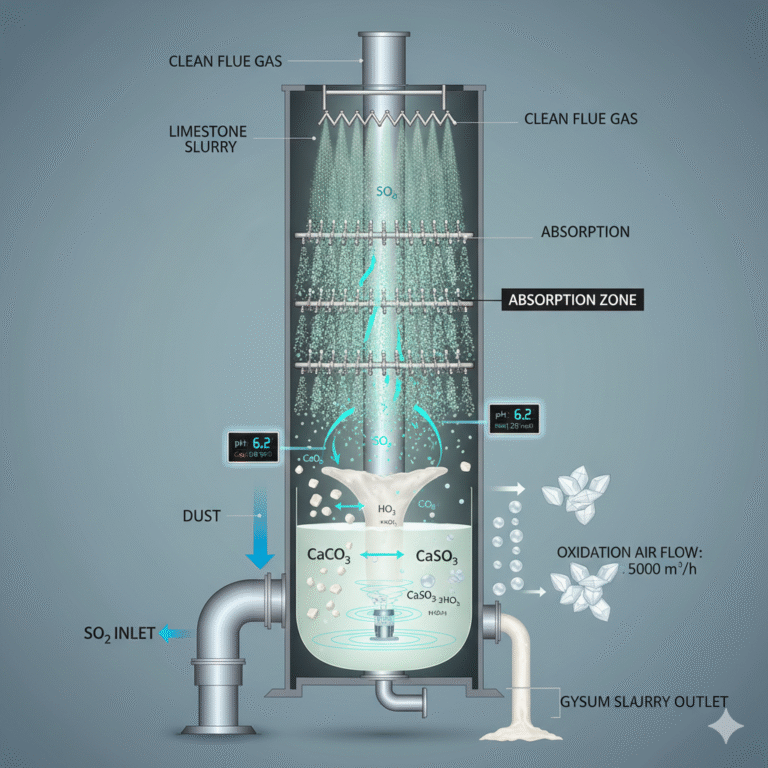

1. The Essence of the Absorption Process

In the absorption tower, sulfur dioxide (SO₂) is absorbed and reacts with limestone, typically achieving an efficiency of 95-99%. The efficiency of this process is limited by three main factors:

First: Gas-liquid absorption rate, which is the ability of sulfur dioxide to penetrate the gas film and dissolve into the liquid phase. The process is faster if the liquid droplets are smaller, spraying is more uniform, the contact area is larger, and the gas velocity is optimal.

Second: Limestone dissolution and neutralization rate. Limestone is a solid, and calcium ions must first dissolve to neutralize the acid. The finer the particles, the faster the dissolution, and the higher the calcium content, the better the reaction. A higher pH value, better agitation, and fewer impurities also aid in faster dissolution.

Third: Oxidation rate. Oxidation air helps convert sulfite into sulfate. Adequate oxidation ensures that gypsum forms with the correct crystal structure. Incomplete oxidation, low agitation, or insufficient airflow leads to poor gypsum formation, dehydration difficulties, and increased wear on circulation pumps.

In actual operation, these three factors are interdependent. For example, insufficient spray flow may cause incomplete absorption and insufficient slurry renewal at the bottom of the tower, leading to an accumulation of sulfite. Similarly, slow limestone dissolution can stabilize the pH but decrease effective alkalinity, causing efficiency to decline. Inadequate oxidation can result in high sulfite levels, black slurry, poor gypsum formation, and increased circulation pump wear.

The essence of an engineer’s daily adjustments is finding a dynamic balance among absorption speed, dissolution speed, and oxidation speed.

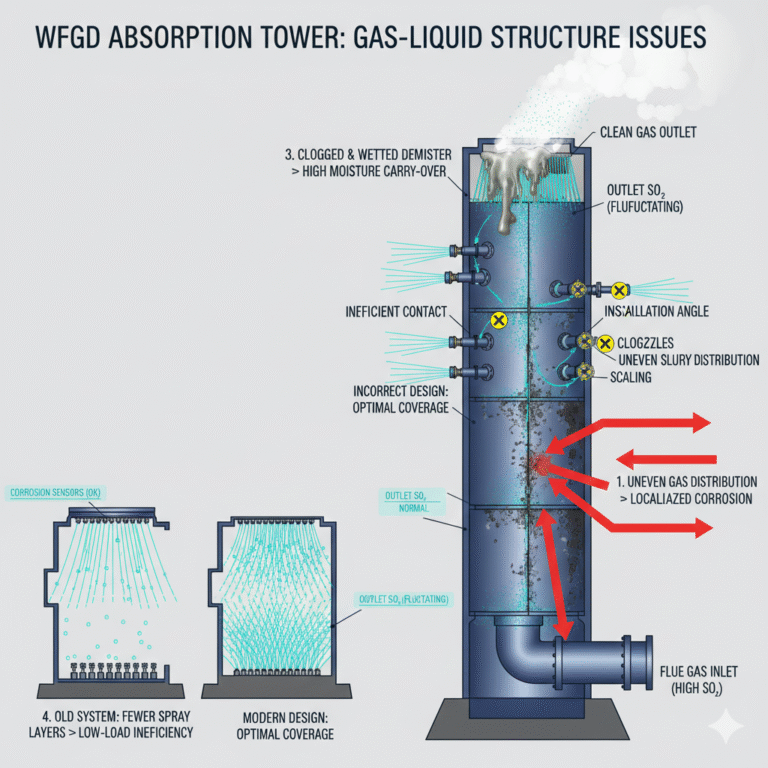

2. Gas-liquid Structure Inside the Absorption Tower

Many technical problems may seem related to specific instrument parameters but are actually caused by issues with the gas-liquid distribution inside the tower.

1. Uneven gas distribution: This manifests as fluctuating SO₂ concentrations at the outlet, delayed response to spray adjustments, and localized corrosion or scaling on the duct walls. The primary cause is poor flow distribution design at the inlet to the absorption tower, which can cause uneven spray coverage and insufficient gas contact in certain areas.

2. Uneven slurry distribution: This results in fluctuating efficiency, rapid scaling or erosion in certain spray zones, and repeated issues after nozzle replacement. The cause lies in improper nozzle selection, installation angle deviations, and blocked nozzles, which reduce the effective contact area of the spray layer.

3. Insufficient demister efficiency: This is indicated by high moisture content in the outlet gas, excessive white smoke, and increasing duct corrosion. The demister blades may be clogged, scaled, or wetted by slurry, increasing the amount of spray liquid carried out and worsening corrosion.

4. Improper spray layer arrangement: Older systems may have fewer spray layers and struggle with desulfurization efficiency at low loads. These gas-liquid structure issues may not appear on the monitoring interface but are critical for long-term stability, maintenance, and equipment lifespan.

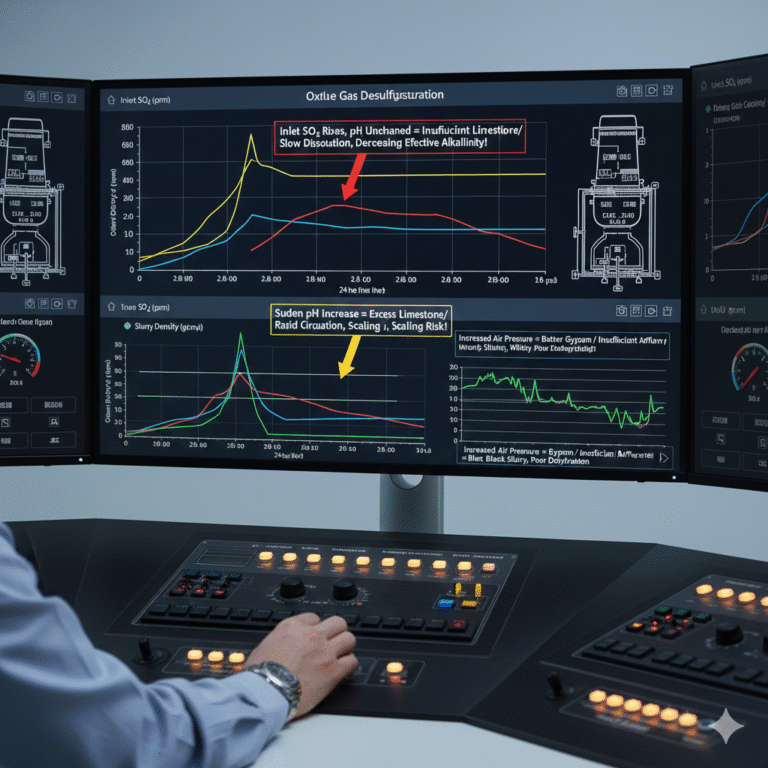

3. The Core Logic of Control Parameters

Engineers often focus on instantaneous values such as pH, slurry density, oxidation air pressure, and pump currents. However, wet desulfurization is a system characterized by large time lags, strong coupling, and slow responses, making it more suitable to observe from a “trend + correlation” perspective.

For example, regarding pH:

If the inlet SO₂ rises but the pH of the tower remains unchanged for a long time, it suggests that limestone supply is insufficient or dissolution is slow. The pH may remain stable, but effective alkalinity is decreasing.

A sudden pH increase suggests that too much limestone has been added or the circulation rate has increased too rapidly, leading to localized oversaturation and scaling risks.

Slurry density changes reflect the status of the tower bottom:

Rapid density increases that are difficult to decrease indicate insufficient slurry discharge at the bottom, leading to potential blockages or “buried nozzles.”

A sudden and rapid decrease in density indicates an influx of new slurry, potentially washing out old slurry, leading to “white discharge” risks and fluctuating efficiency.

Oxidation air pressure does not always correlate with better results:

Increasing air pressure does not necessarily improve gypsum crystal structure; in fact, excessive pressure may disturb the slurry and introduce air bubbles, increasing dehydration load.

Insufficient airflow leads to high sulfite levels, black slurry, and poor gypsum formation, making dehydration difficult.

The key for experienced engineers is not focusing on the exact values but understanding whether the changes in SO₂, pH, density, and air pressure are logically consistent over time.

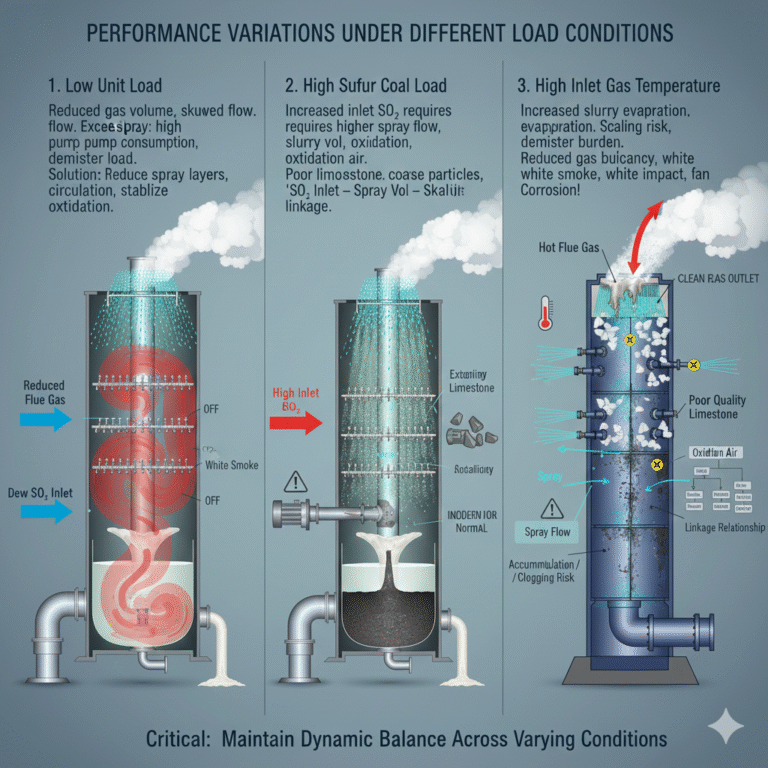

4. Performance Variations Under Different Load Conditions

Wet desulfurization does not operate under “rated conditions” but must adapt to constantly changing external conditions.

Unit load variations: At low load, the gas volume is reduced, but the flow field inside the tower may become skewed or form dead zones. In this case, excessive spray can increase pump consumption and demister load, reducing efficiency. It is necessary to appropriately reduce the number of spray layers and circulation volume, keeping oxidation air stable to avoid “extinguishing and reigniting” fluctuations.

Coal sulfur fluctuations: High sulfur coal increases inlet SO₂, and spray flow, slurry volume, and oxidation air must keep pace, or the bottom of the tower may become clogged. Poor-quality limestone exacerbates the problems of coarse particles, low activity, and impurities. This situation requires establishing a “SO₂ inlet – spray volume – slurry volume” linkage relationship and using staged adjustments when necessary.

Inlet gas temperature changes: Higher gas temperatures lead to faster slurry evaporation, increasing the risk of scaling in the tower and burdening the demister. Lower gas temperatures reduce gas buoyancy, causing droplets to remain suspended and increasing white smoke, which may affect the draft fan performance.

Wet gas emissions make the flue duct and stack more sensitive to corrosion. Any demisting problems quickly reflect as corrosion or white smoke in the stack, requiring better demister efficiency and higher corrosion protection standards.

5. Root Causes of Common Failures

Each failure often has a systematic underlying cause:

Nozzle clogging: This appears as large particles and debris. The root cause is often poor screening in the slurry preparation system, screen damage, or ineffective bypass control, causing slurry to settle and form hard particles.

Severe scaling inside the tower: This results from excessive limestone, high pH, insufficient oxidation air, uneven agitation, or high sulfite levels, leading to deposition.

Difficult gypsum dehydration: This is typically due to incomplete desulfurization reactions, high sulfite and soluble salt levels, or overly fine gypsum crystals that form tight filter cakes.

Circulation pump wear: Often due to large slurry particles, poor oxidation, high sedimentation density, or impacts on the pump impeller during startup or shutdown.

6. Gypsum Crystal Form and By-product Value

Many systems only focus on whether the gypsum can be expelled, neglecting its crystal form and usability. The crystal form directly affects the ease of dehydration, the marketability of by-products, and the load and lifespan of dehydration equipment.

7. System Coupling

Wet desulfurization is closely related to the upstream and downstream systems. Many issues that seem like desulfurization problems are actually affected by these interconnected systems.

8. Deep Optimization Directions

Real deep optimization doesn’t necessarily require large-scale modifications but more often involves strategic and detailed adjustments.

Conclusion

Limestone wet desulfurization is often considered a standardized technology. However, it involves complex engineering issues such as gas-liquid mass transfer, solid dissolution, crystal structure control, flow distribution, and system coupling. Engineers who truly understand these underlying principles can achieve stable emissions compliance, reasonable energy consumption, balanced equipment load, preventative maintenance, and valuable by-products.