In many mission-critical environments—industrial plants, data centers, commercial buildings, control rooms, and other facilities where power loss is unacceptable—a dual power supply system is essential.

However, in practical engineering, “dual power” is far more than simply connecting two power sources. It is a complete system involving power sources, switching mechanisms, interlocking protection, load compatibility, and periodic testing. Any mistake in these areas can lead to switching failure, back-feeding faults, equipment reverse rotation, or even catastrophic damage.

This article provides a clear and practical explanation of the key principles and engineering considerations behind reliable dual-power systems.

1. What Dual Power Supply Truly Means

The purpose of a dual power supply system is simple:

When the main power source becomes abnormal (power outage, undervoltage, overvoltage, phase loss, etc.), the backup power source must take over safely and reliably, with minimal interruption.

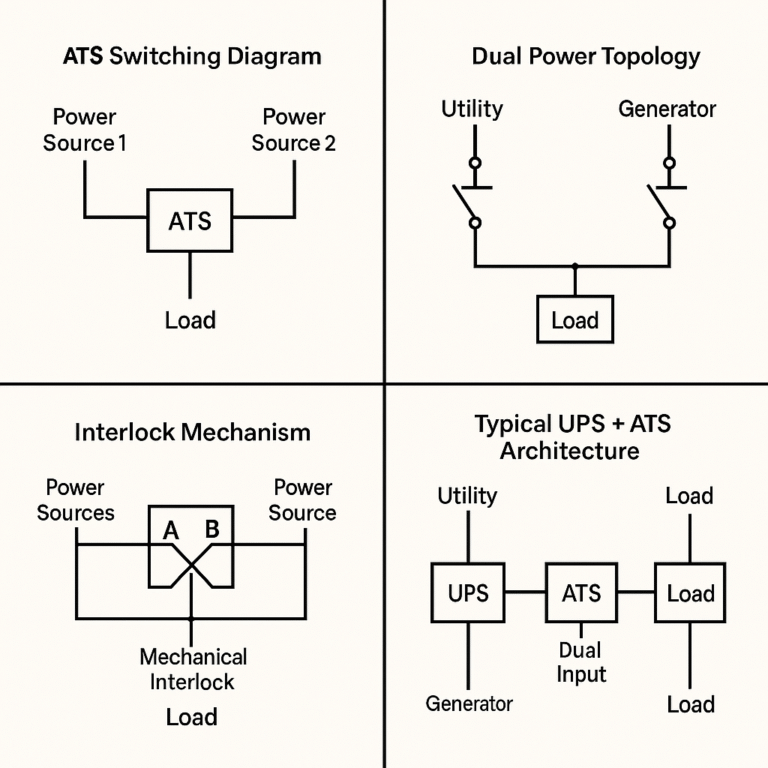

A complete system usually includes:

Two independent power sources

(e.g., Utility + Generator, Utility + UPS)A switching device

Most commonly an Automatic Transfer Switch (ATS)Control logic and interlocking protections

The key insight:

The value of dual power supply lies not in “having two sources,”

but in switching safely and correctly.

This is the part often overlooked in design and installation.

2. Common Dual Power Supply Configurations in the Field

Different loads have different tolerance levels for power interruption.

Therefore, there is no universal solution—the system must match the load type.

2.1 Manual Transfer Switch (MTS)

Suitable for general loads such as pumps or fans.

Low cost but requires manual operation.

2.2 Automatic Transfer Switch (ATS)

The most common solution in industrial and commercial systems.

Automatically detects main power health conditions and switches to the backup source when needed.

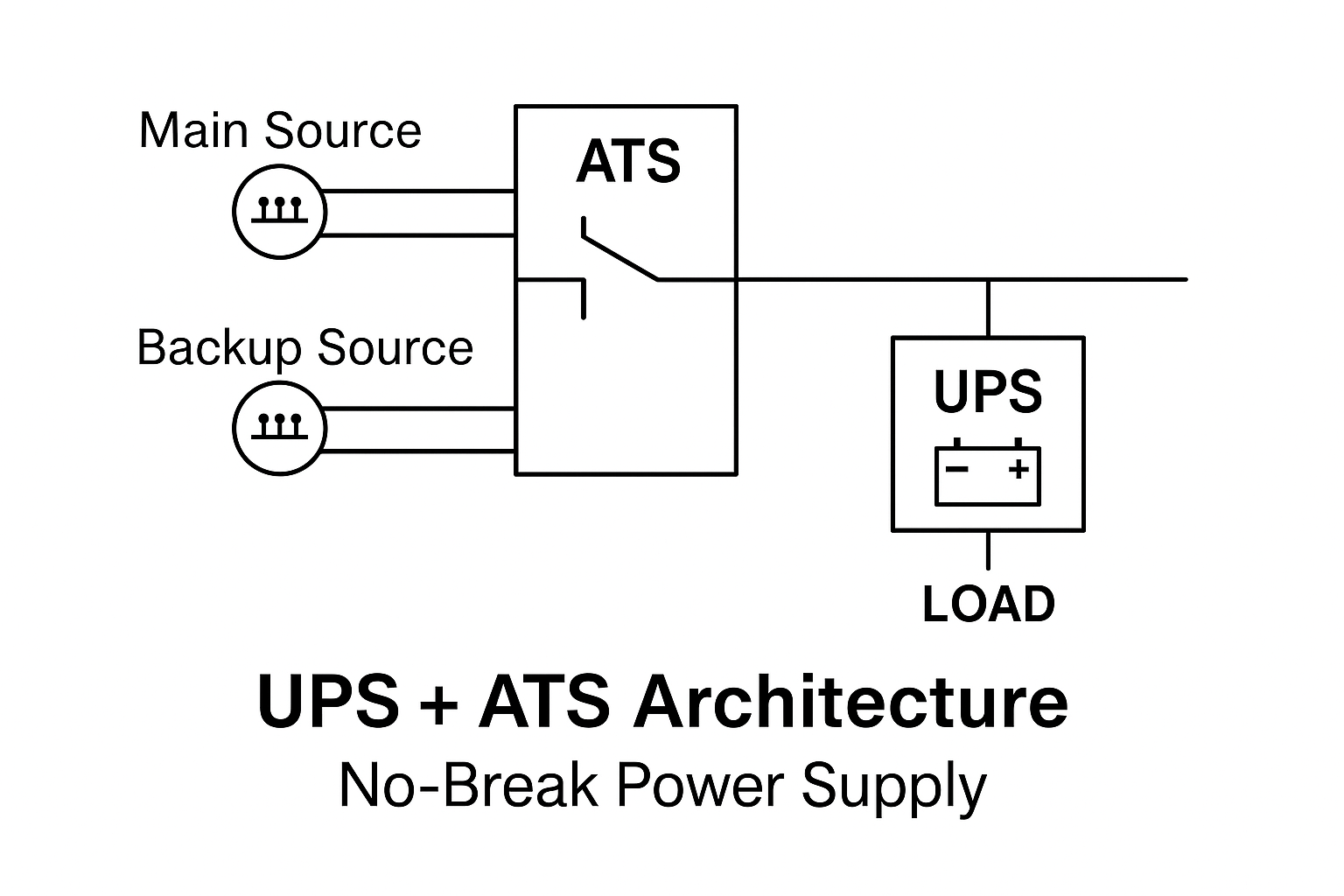

2.3 UPS + Dual Input Combination

Used when zero interruption is required, such as:

IT servers

Medical equipment

Communication systems

In this setup, the ATS handles source switching, while UPS ensures zero-downtime output.

2.4 Dual-Feeding or Ring Network System

Typical in large industrial plants and residential grids.

This is not a simple “switching” scheme but a system-level redundancy design.

3. Engineering Essentials for Reliable Switching

To guarantee safe and reliable transfer between power sources, several technical aspects must be handled correctly.

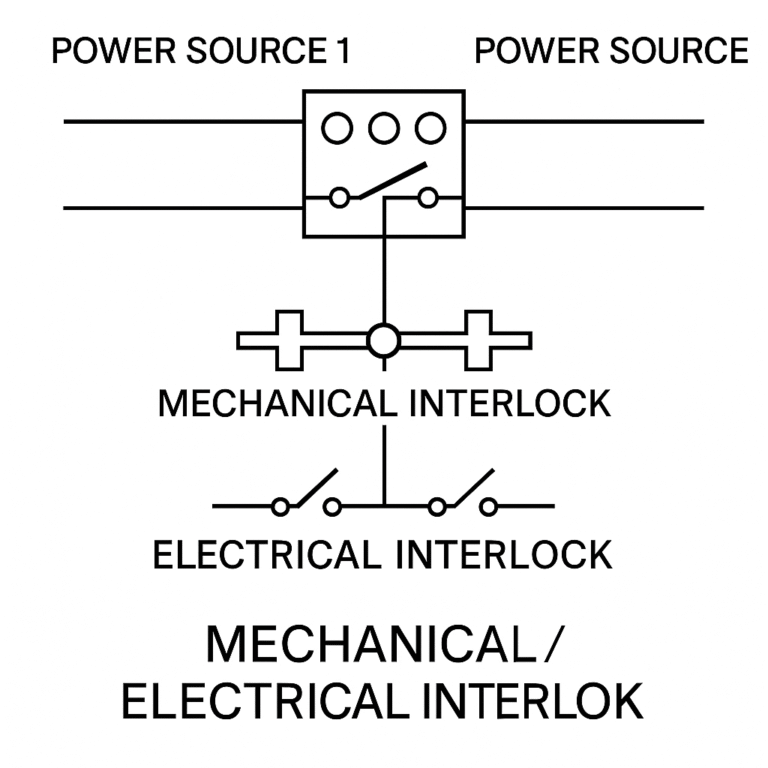

3.1 Interlocking Must Be Robust

Regardless of topology, the two sources must never feed the load simultaneously.

A reliable system requires both:

Mechanical interlock

Electrical (control) interlock

Both are necessary to avoid back-feeding short circuits.

3.2 Proper Evaluation of Power Source Health

A correct switching decision must evaluate:

Undervoltage

Overvoltage

Phase imbalance

Phase sequence abnormalities

Complete power failure

Failing to monitor these conditions may cause:

Early/false switching

Delayed switching

Equipment failures due to abnormal voltage

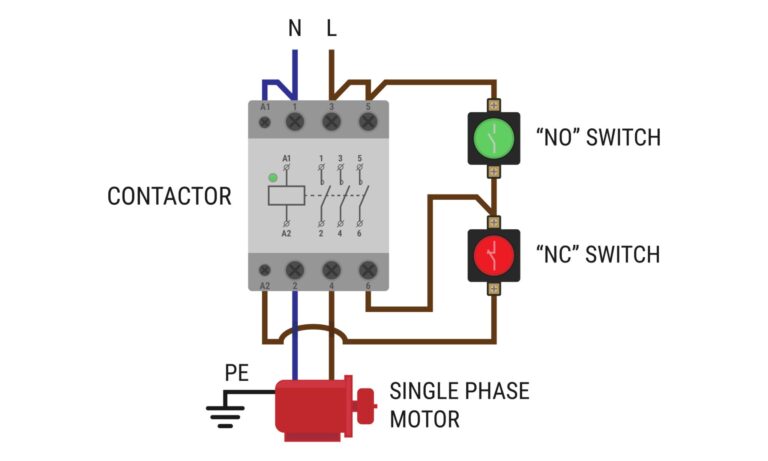

3.3 Switching Time Must Match Load Characteristics

Different loads tolerate different switching behaviors:

Motors: may generate reverse EMF; forced fast switching may damage equipment

Precision loads (UPS output): require seamless switching

Lighting or fans: can tolerate short interruptions

Faster is not always better—matching the switching mode to the load is essential.

4. Frequent Problems in Real-World Projects

In practice, failures often come from installation or configuration issues rather than device defects.

4.1 Two “independent” sources coming from the same upstream line

This provides no real redundancy and is a common hidden risk.

4.2 Insufficient backup power capacity

If the generator or backup source is undersized, switching will cause immediate tripping or overload.

4.3 Only electrical interlock, no mechanical interlock

A control failure can result in both sources being connected simultaneously.

4.4 Incorrect phase sequence leading to reverse rotation

This is especially critical for pumps or fans.

4.5 Lack of periodic load testing

A backup source that is never tested will almost certainly fail when needed.

Diesel generators, in particular, require regular load runs to avoid carbon buildup and capacity degradation.

These issues are not “advanced” technical problems—they are typical execution errors.

5. Conclusion

In industrial and commercial environments, the dual power system is the “lifeline” of critical loads. What matters is not merely having two power sources, but ensuring:

Proper design

Reliable interlocking

Correct switching logic

Load compatibility

Regular testing and maintenance

A well-designed dual power system can operate for years without failure.

A poorly designed one may fail precisely when it is needed most.

Understanding these engineering principles enables technicians and engineers to design, operate, and troubleshoot dual-power systems with greater confidence.