Introduction

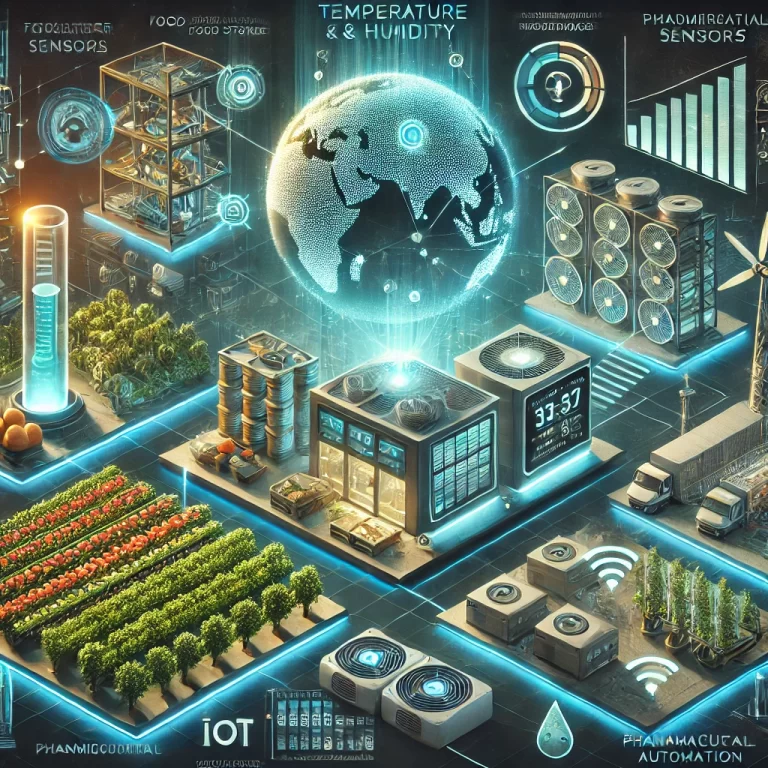

Sensors are critical components in modern technology, designed to detect specific physical or environmental changes and convert this information into electrical signals or other readable outputs. This capability supports various applications such as data transmission, processing, storage, display, recording, and control. Modern sensors exhibit key features including miniaturization, digitization, intelligence, multifunctionality, system integration, and networking. They serve as fundamental elements for automatic detection and control systems.

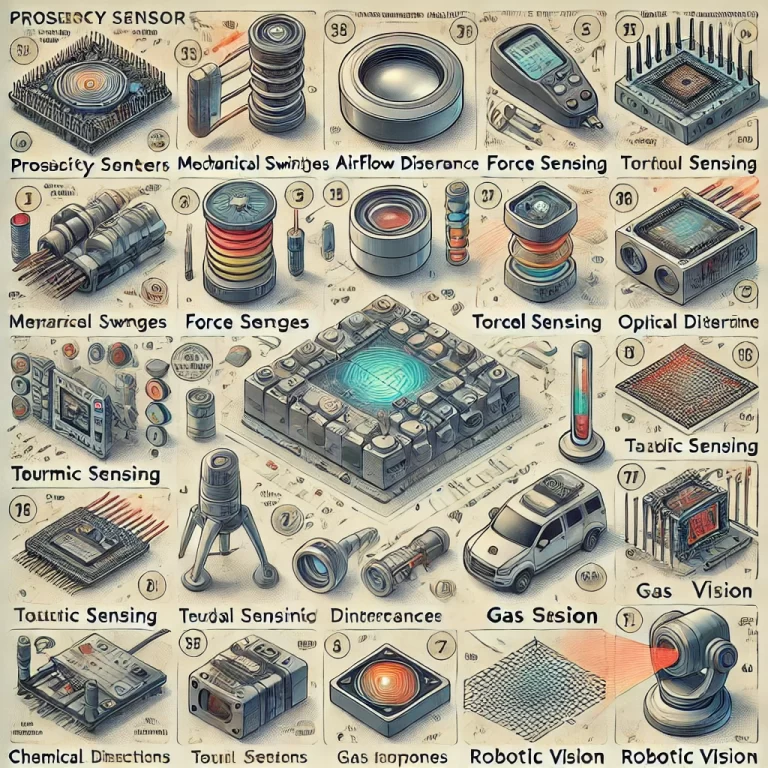

Major Classifications of Sensors

By Application

Pressure and Force Sensors: Measure pressure and mechanical force in various systems.

Position Sensors: Detect the physical position of objects.

Level Sensors: Monitor fluid or solid material levels in containers.

Energy Consumption Sensors: Track and record energy usage.

Speed Sensors: Measure the rate of movement.

Acceleration Sensors: Detect changes in velocity.

Radiation Sensors: Measure radiation levels.

Thermal Sensors: Detect temperature variations.

2. By Operating Principle

Vibration Sensors: Monitor mechanical vibrations.

Humidity Sensors: Measure moisture levels.

Magnetic Sensors: Detect magnetic fields.

Gas Sensors: Identify and measure gas concentrations.

Vacuum Sensors: Measure vacuum pressure.

Biosensors: Analyze biological and chemical substances.

3. By Output Signal Type

Analog Sensors: Convert physical quantities into continuous electrical signals.

Digital Sensors: Transform measured values into discrete digital outputs.

Quasi-Digital Sensors: Output frequency or pulse-based signals.

Switch Sensors: Trigger high or low signals when a threshold is crossed.

4. By Manufacturing Process

Integrated Sensors: Utilize semiconductor IC manufacturing technology, often integrating signal processing circuits.

Thin-Film Sensors: Formed by depositing sensitive thin films on substrates.

Thick-Film Sensors: Created by applying paste materials onto ceramic substrates, followed by heat treatment.

Ceramic Sensors: Produced through ceramic processes involving sintering at high temperatures.

5. By Measurement Target

Physical Sensors: Rely on changes in physical properties.

Chemical Sensors: Convert chemical properties into measurable signals.

Biological Sensors: Detect and analyze biological components.

6. By Structure

Basic Sensors: Simple transducers.

Combined Sensors: Assemblies of multiple transducers.

Application-Specific Sensors: Integrated with other components for specialized uses.

7. By Operating Mode

Active Sensors: Emit signals to interact with the target (e.g., radar systems).

Passive Sensors: Detect naturally emitted signals (e.g., infrared thermometers).

Selection Principles for Sensors

Choosing the right sensor requires evaluating multiple factors to ensure compatibility with the measurement task. Consider the following aspects:

Measurement Range and Scale: Select a sensor with a suitable range for the intended measurement.

Size and Installation Constraints: Ensure the sensor’s physical dimensions fit the application environment.

Contact vs. Non-Contact Measurement: Determine whether the sensor needs to physically interact with the target.

Signal Transmission Method: Decide between wired or wireless data transmission.

Source and Cost: Weigh the trade-offs between domestic and imported sensors regarding price and availability.

Key Performance Criteria

Sensitivity

A high sensitivity sensor provides stronger output signals for small input changes. However, excessive sensitivity may introduce noise, so selecting sensors with a high signal-to-noise ratio is crucial.

Frequency Response

Sensors should maintain accuracy within the required frequency range. Faster response times improve dynamic measurement accuracy.

Linearity

Ideal sensors have a direct proportional relationship between input and output within a defined range, ensuring precise measurements.

Stability

Stability refers to a sensor’s ability to maintain consistent performance over time. Environmental adaptability is crucial for long-term reliability.

Accuracy

Precision must align with system requirements. High accuracy often comes with higher costs, so selecting an appropriately accurate sensor is essential.

Conclusion

Sensors are foundational to technological systems, and understanding their classifications and selection criteria ensures optimal performance. By thoroughly evaluating application needs and sensor characteristics, engineers can make informed decisions to support system efficiency and reliability.